“Supposed To Be Dead…” Retracing A Wounded Artillerist From The Battle Of Fredericksburg

Museum members support scholarship like this.

Around noon on December 13, 1862, a fourteen-gun battery of the Confederate Army unleashed a murderous torrent upon an estimated 8,000 Union Army infantrymen. Positioned atop the crest of Prospect Hill – the Confederate’s right flank some four miles southeast of the besieged city of Fredericksburg, Virginia – these Rebel guns quickly decimated Yankee footsoldiers on an open field opposite the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac (RF&P) railroad. “[Union] columns went down like wheat before the reaper,” recalled one cannoneer. “Another and another quick volley in quick succession completed the work.”[1] Across the open field, Union artillery swiftly responded with thundering barrages of smothering counter-battery fire.

“The air was resonant with the savage music of shells and solid shot,” remarked one Confederate eyewitness. “The white smoke-wreaths of exploding shells were everywhere visible.”[2] Forced to interchangeably cannonade unrelenting Union infantry and their menacing artillery, the fatigued and ammunition depleted fourteen-gun battery was relieved by 3:30pm. Shortly thereafter, Confederate Lieutenant General Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson marshaled his reserves into the fray. Among the new Dixie artillerists was twenty-year-old William Henry Cash, a Private in the 2nd Rockbridge Artillery.

Born in 1842 near the unincorporated communities of Vesuvius and Steeles Tavern, the Shenandoah Valley native had fought with the Confederate Army since August 1861, most notably at the Battle of Allegheny Mountain and Jackson’s Valley Campaign. Now atop Prospect Hill, Cash withstood an unfathomable iron onslaught. Dodging torrents of bedeviling shell fragments, as well as exploded shrapnel-like chunks of frozen earth, the gray-coated gunners waged a fierce duel for dominance against their blue-coated rivals.

“A shell hit a Confederate cannon, killing and wounded nine members of the crew……a[nother] shell caught a Virginia gunner between the shoulder blades and flung his lifeless body three feet into the air.”[3] Projectiles that overshot the Rebel cannons saturated a nearby ravine, inadvertently bludgeoning scores of their horses. “One poor animal,” a Virginia officer reflected, “was walking about with all of that portion of his face below his eyes entirely carried away by a solid shot or shell.”[4] Such unsettling images branded Prospect Hill’s inseparable name: Dead Horse Hill.

As daylight faded, Jackson hastily ordered ten batteries – to include the 2nd Rockbridge Artillery – down the slopes for a twilight assault. “The [Confederate] artillerymen muscled their unwieldy guns across the [RF&P] railroad and dropped trails on the fringe of the plain.”[5] From a position near his Rockbridge gunners, the Confederate commander observed the luminous spectacle. Promptly answered by the ever-pestilential Union batteries, Jackson quickly countermanded his order to attack. His artillerists returned their guns to their earthworks atop Prospect Hill where they bivouacked for the frigid December night without fire. The now corpse strewn field below them became known ever after as Slaughter Pen Farm.

The 2nd Rockbridge Artillery suffered seven men wounded (including Cash) during the two hours the battery was engaged.[6] At some point, a shell fragment struck Cash’s head, carried away a section of the skull, and exposed his brain. Such a ghastly injury was not uncommon among those maimed during the Fredericksburg campaign. One nurse recounted a similar wound that befell a Union solider. “A shell had taken part of his skull away, about as large a piece as a dollar…I could see the pulsation of the brain, and when he talked I could see a movement of the same, slight though it was.”[7]

Miraculously, Cash survived, partly from luck and the careful planning of Lafayette Guild, Surgeon and Medical Director of the Army of Northern Virginia. The previous day of battle, Guild had telegraphed Samuel P. Moore, the Confederate Surgeon General. “Some definite and well-regulated system of railroad transportation should be adopted for the wounded.”[8] Lacking a sufficiency of field hospital tents, and without a nearby location for mass treatment, Guild concluded, “it will be necessary to have the wounded rapidly conveyed to Richmond.”[9] Subsequently admitted to a hospital within the Confederate capital, Cash was undoubtedly among those transported south.

Further details of Cash’s military service are chiefly found on muster rolls of the Rockbridge artillerists:

December 31, 1862 – “wounded and missing since the Battle of Fredericksburg.”

February 28, 1863 – “absent, supposed to be dead since heard from.”

Curiously, Cash is reported to have rejoined his battery sometime in September 1863 – which, by then, included his younger brother – and remained with his fellow Rockbridge gunners until November 27, 1863. Reported sick shortly thereafter, Cash remained absent from his battery for the remainder of the war.[10]

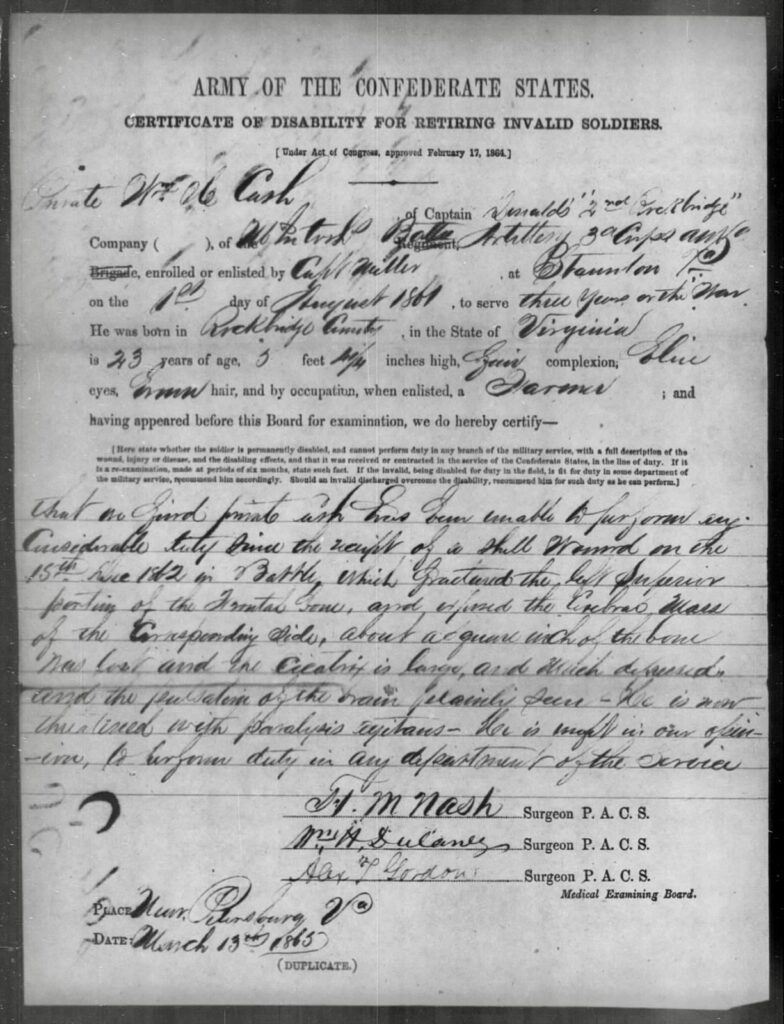

On March 1, 1865, William Cash penned to a Confederate Colonel, “I most respectfully ask for a form to appear before a medical examining board to be retired from service on account of a wound received near Fredericksburg…”[11] A First Lieutenant of the 2nd Rockbridge Battery endorsed Cash’s request, adding, “his skull bone being badly broken…a piece of it of considerable size taken out.”[12] Hard-pressed for new troops, however, Rebel commanders likely scrutinized all such initiatives that would surely deplete their ranks. On March 4, 1865, a Confederate officer noted on Cash’s request, “if unfit for duty in the field but capable of performing duty in some department of the service, the [medical examining] board will specify for what position he is best qualified.”[13]

On March 13, 1865, three Confederate Army surgeons near Peterburg, Virginia signed a Certificate For Retiring Invalid Soldiers, which approved Cash’s medical discharge. “We find Private Cash has been unable to perform any considerable duty since the receipt of a shell wound…which fractured the left superior portion of the frontal bone and injured the cerebral mass of the corresponding side. About a square inch of the bone was lost and the cicatrix is large and much depressed and the pulsation of the brain plainly seen. He is now threatened with paralysis agitans. He is unfit in our opinion to perform duty in any department of the service.”[14]

Discharged less than a month before the collapse of the Confederacy, William Cash spent his remaining years in Rockbridge County, Virginia with his wife and children. He died in 1923, two weeks shy of his eighty-first birthday. Of note, Cash’s injury appears in Volume 2 of The U.S. Army’s Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, published by the War Department in 1870.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Kyle Nappi is the great-great-great-great-grandnephew of William Henry Cash. An alumnus of The Ohio State University, Kyle serves as a national security policy specialist in the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. He is also an independent researcher and writer of military history (chiefly the World Wars), having interviewed ~4,500 elder military combatants across nearly two-dozen countries.

Endnotes

[1] Paul Taylor, Glory Was Not Their Companion: The Twenty-Sixth New York Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War, (Jefferson: McFarland & Company, 2015), 96.

[2] U.S. Department of War, The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume 21, Chapter 23, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1902), 424.

[3] Francis Augustín O’Reilly, The Fredericksburg Campaign: Winter War on the Rappahannock, (Batton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006), 424.

[4] William Page Carter, “Dead Horse Hill,” The Home-Maker, Volume 3, (New York: The Home-Maker Company, 1889), 304.

[5] Frank A. O’Reilly, “Stonewall” Jackson at Fredericksburg, The Battle of Prospect Hill, December 13, 1862, (Lynchburg: H. E. Howard, Inc., 1993), 178.

[6] Robert J. Driver, Jr., The 1st and 2nd Rockbridge Artillery, 1st Edition, (Lynchburg: H. E. Howard, Inc., 1987), 108.

[7] Maureen Lavelle, “‘Ready for Mischief’ Dr. Mary Walker and her Service during the Civil War”, The National Museum of Civil War Medicine, December 12, 2016, https://www.civilwarmed.org/walker/.

[8] The War of the Rebellion, 557.

[9] Ibid.

[10] “Confederate Soldiers from the State of Virginia – Cash, William H – Capt. Donald’s Co., Light Artillery,” Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Virginia, Record Group 109, Microcopy 324, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, D.C., https://catalog.archives.gov/id/97638851, Accessed March 27, 2021.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

Tags: Artillery, Civil War Medicine, Fredericksburg, Kyle Nappi, William Henry Cash Posted in: Battlefield Medicine