The Story of the Pile of Limbs

Help us preserve some of the prosthetic limbs in our collection by supporting our “Arm and a Leg Campaign”

Robert G. Slawson, MD, FACR

Originally published in 2017 in the Surgeon’s Call, Volume 22, No.1

Battlefield wounds during the Civil War were a significant problem regardless of the body part involved.1 Death frequently followed, regardless of location of the wound. The principle causes of death from wounds were: exsanguination (severe blood loss) and infection. Existing surgical techniques were not adequate to treat wounds in the head, chest, and abdomen; and the majority of men who received such wounds would die. Wounds to the extremities could be better dealt with.

Treatment and cleaning of the wound within forty-eight hours was necessary to decrease the risk of dying from infection, but it must be remembered that all this happened before the widespread recognition of bacteria as a cause of disease. Unfortunately, the use of antiseptics in wound debridement was not yet routine and would not be until after 1867. For most wounds, surgery was indicated to clean out the wound, removing fragmented bullets and other foreign materials, as well as all damaged bone and soft tissue.1,2 Parts of the body where debridement could most easily be done were the extremities and the edges of the trunk. Accordingly, soldiers with such wounds were the ones most often removed from the battlefields to the field hospitals for urgent medical care as the first step in the exercise of triage.

Wounds were caused by many different types of weapons. Cannon fire with the associated shrapnel and grape shot was deadly, as was the concussive force of the cannon ball passing close to an individual. Edged weapons such as swords and bayonets caused severe wounds, often with marked internal bleeding which were frequently fatal. It is not possible to state the percentage of the deaths caused by any type of weapon because only the living, potentially treatable, and hopefully salvageable, wounded were removed from the battlefields and ultimately sent to the field hospitals, where the initial medical records were recorded. Therefore, there is no record of cause of death for most of the dead left on the battlefield.

Musket balls were responsible for many of the dead and a larger part of the wounded. While the smooth-bore musket ball, when fired from an appropriate range, could cause severe damage, the greater part of musket ball damage came from the new rifled musket, which fired the newly-designed Minié ball. This ball was elongated and hollow at the base so that it could expand to engage the rifling grooves in the musket barrel. This increased the accuracy and effective range of firing and resulted in many more casualties than with the smooth-bore musket.

The Minié ball was made of soft lead and, weighing more than an ounce, was more than one-half inch in diameter. When it hit bone, the bone was shattered for several inches and the bullet often fragmented as well. A tremendous energy was also deposited in the muscle and soft tissue, which cause severe nerve and muscle damage. Unfortunately, the bullet had a relatively slow velocity compared to modern weapons and the entry wound was not sterile. In fact, a lot of surface debris was carried into the wound including bits of clothing, dirt, and even oil and packing from the musket. In effect, the wound created an excellent tissue culture medium and then filled it with bacteria to make certain that it became infected.

When wounds were in the extremities, they could be surgically cleaned more easily. When the nerves and vessels were damaged, amputation gave the best chance of survival.3 The surgery actually accomplished two things: the damaged blood vessels were tied to stop the bleeding; and the damaged tissue and bone were removed, as well as any other material in the wound. When the arterial blood supply to the extremity was completely destroyed, all tissue distal to it would die, thus making amputation necessary. The further the wound was from the shoulder or the hip, the greater the chance of survival and the better the chance to save a portion of the limb. When major nerves were destroyed, as they often were, amputation was called for since any remaining part would not be able to function; and the denervated extremity would wither and become stiff. Certainly the most important reason for surgery was adequate cleansing of the wound. Leaving damaged and contaminated tissue or doing an inadequate amputation would make further surgery necessary and significantly decrease chances for survival. It is true that local infection in the wound usually followed anyway, but this was often without the development of generalized systemic infection.

Necessary amputations had been done for some time. During the Napoleonic wars, amputation was practiced even though effective anesthesia was not available. It was the fastest way to treat the largest number of wounded in a very short window of time. They had found that forty-eight hours after the injury was the magic time. After that, the probability of dying from infection was very high. During the Crimean War in the mid-1850s, it had been demonstrated again that primary amputation was the best way to save the most lives.4 They also found that amputations done days later were seldom as effective in preventing death.3,5 Because of this fact, early amputation became the recommended treatment in the Civil War. Resistance to this was frequent among surgeons at the beginning of their service and many conservative approaches were tried. Most of these ended fatally. Many surgeons who initially opposed amputation came to see the benefits of this procedure in survival.6

Because of the devastating effects of amputation on the lives of most of the survivors, the public objected to this treatment. The term “invalid” actually meant that the person was an incomplete person and not a valid person. Certainly it was difficult for a laborer or a farmer to function well afterwards, especially if the limb was an arm. A huge public outcry arose. Many both in and out of the army complained that surgeons were too quick to amputate. In the early part of the war, some unnecessary amputations may have been done by inexperienced surgeons or by some who simply wanted the experience of learning to do amputations. The army responded to this and developed criteria for amputation to limit the procedure to those in whom it was medically necessary. Military surgeons came to be called “sawbones,” a nickname that is still applied to surgeons, although most people don’t realize the origin of the term.

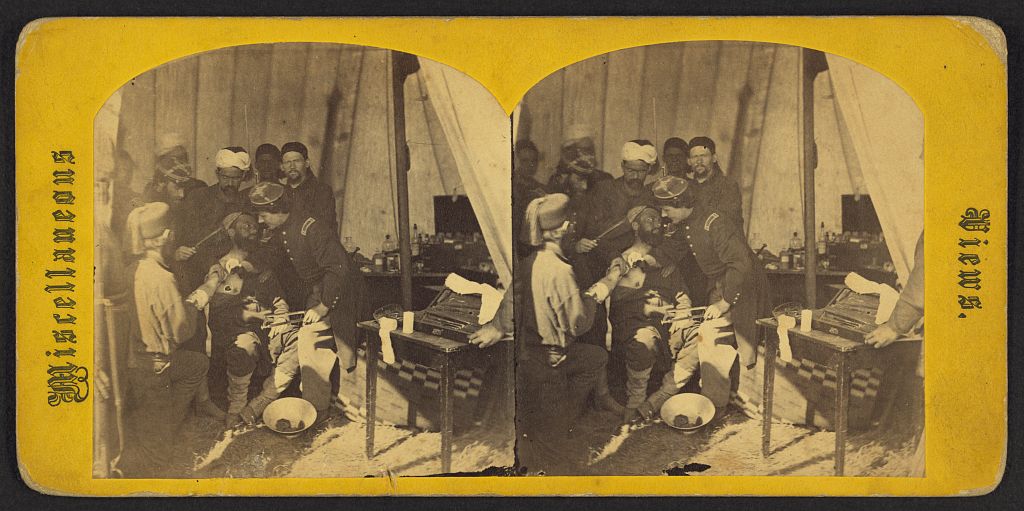

After a battle, surgeons at the field hospitals spent hours treating the wounded that arrived at their doors. There were few skilled operators and many patients who needed their care. Surgery was performed expeditiously and amputation was the usual operation when the extremity had been injured.1 An amputation took only a few minutes. When the surgery for one patient was completed, another patient was waiting for the operating table. The amputated limbs, at times, accumulated in piles near the operating table before they could be disposed of. This was a gruesome sight and caused comments by uninvolved observers. Such piles of limbs were known to have existed as early as 1811, described by a British officer at a British hospital in France during the Napoleonic wars, at a time when surgery was being done without anesthesia.7,8

Certainly the piles of limbs at the field hospitals is described in most secondary sources and in general accounts of the war.2 Several questions arise from these mentions. How frequently were these piles accumulated? Was this a universal phenomenon or only an occasional occurrence? What happened to the limbs after surgery? To where were they removed? To find answers to these questions, a large number of hospital descriptions, letters, memoirs, and diaries have been reviewed. Most of these reports were not published until many years after the war and the question always arises whether the observation of piles of limbs was personal knowledge or was added later because of the popular belief.

The question of the frequency of these piles is easy to answer, although not with any precision. The majority of letters, diaries, and memoirs of accounts of field hospitals do not mention piles of limbs.9-78 Of the individuals writing on the subject, six were surgeons in the war21,24,27,52,54,71 and six were nurses.53,55,56,63,65,72 Many reports do not even mention military hospitals, although they were certainly aware of them and often in them. Clearly they only discuss things that concerned them and the accumulating piles of limbs were part of everyday work at field hospitals. There are, however, a number of accounts that do describe piles of limbs either by the operating table or on the ground outside the window closest to an operating table.79-92 Some of these descriptions are by surgeons.82 Two accounts are descriptions of medical care at a battlefield.87,93 Many of the descriptions are clear enough to demonstrate that after battles with large numbers of wounded and many operations, such piles of amputated limbs did appear.

The question of disposal of the limbs is much more difficult to answer, since very little information is available. It would be reasonable to believe that most physicians would regard the patients and their parts with humanity, and because of this, burial would subsequently be performed. Many hospitals were near or in churches and a cemetery would be nearby. In addition, burial details were constantly at work to bury those who were killed on the battlefield or died soon after. The amputated arms and legs would simply have been buried as part of the routine. Five of the sources specifically address this issue of burial.80,82,86,89,91 One writer, who was a surgeon at Williamsburg, describes limbs piled as high as the window sills by the end of the day and pits dug each day to bury the dozens of limbs collected.82 He did not, however, state where the limb burial occurred.

Another account is in a history of Keedysville, MD, where the hospital was on the second floor of the church.80 In this case, it is stated that the limbs were buried in the churchyard next to the church, subsequently resulting in damage to the church walls. In only one other account was a specific burial location mentioned. An account by an observant young man from Shepherdstown, VA, (now WV) states that the limbs were carelessly buried when the first rush of surgical work was over,86 although he does not state where the limbs were buried. In 1887 in Frederick, MD, while breaking ground for a new building behind the Frederick Female Seminary, a number of arm and leg bones were found with saw marks on them.94 The article explained that these were undoubtedly from arms and legs buried there while the building was used as a hospital after the Battle of Antietam. It was not thought necessary to re-bury them so they were carted away with the dirt.

Descriptions of many field hospital sites after the battle of Gettysburg, PA, contain seven additional descriptions of piles of limbs, and two of these accounts mention burials of amputated limbs.89 It is stated that the pile of limbs at the Lutheran Theological Seminary field hospital had accumulated for several days before being taken away and buried.89 In the account concerning the Gettysburg Warehouse Hospital, it is stated that men came with horses and carts, collected the amputated parts, and buried them in long trenches.89 However the sites of the trenches are not stated. A new corollary appeared on this subject when, in 1906, while remodeling and enlarging the Adams County Courthouse in Gettysburg, workers discovered a collection of bones of amputated arms and legs apparently buried there while the building was used as the Courthouse Hospital by the Union Army in 1863.95

Perhaps the most unusual account is in a narrative about Ellwood House near Chancellorsville, VA.91 Major General Thomas (Stonewall) Jackson was wounded at Chancellorsville and his arm was amputated at a field hospital near that battlefield. After surgery, the arm was placed on a pile of amputated limbs near the field hospital but was rescued from the pile by Chaplain Beverly Lacy, who carried it to Ellwood House. It was buried in the family cemetery in a marked location. This is the only amputated limb for which a definite burial site is known. Another example of a known destination for an amputated part is General Sickles’ leg. Sickles’ leg was damaged at Gettysburg when he was hit by a cannon ball. After amputation the specimen was prepared and presented to the Army Medical Museum in the Surgeon General’s Office. It is well known that General Sickles organized annual parties to visit his limb on the anniversary of the amputation. This specimen is still on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine.

General Daniel Sickles (center) with General Joseph B. Carr (left) and General Charles K. Graham (right), visiting the location on Gettysburg Battlefield where Sickles was injured. Photograph circa 1886. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

One other note needs to be added. A booklet published in 1964 on military hospitals in Richmond, VA, states that recent digging in the yard at General Hospital #18 revealed leg and arm bones, presumably from amputation burials.96 A later book on the same subject published in 2005 fails to mention such a finding.76

Three weeks after the Battle of Antietam, a farmer found an intact, detached arm while plowing a field.97 Legend has it that he initially placed this souvenir in brine but later passed it to a local physician who put it in formaldehyde. After a period of time the arm reappeared in a small museum near the battlefield. A pathologist examined the arm and stated it was from a 19 year-old man. When the museum closed, the specimen was passed to the NMCWM in Frederick, MD. It is clear that the arm was not surgically removed, but was probably was blown off by a cannon. The fate of the original owner of the arm is not known.

In summary, one must conclude that after the bigger battles when the number of amputations was large, the amputated arms and legs would have accumulated, often not being removed from the vicinity of the surgery until the end of the day or completion of the surgeries. When the clean-up began, these accumulated extremities would be removed to be buried in a convenient location near the operating hospital. Except for Jackson’s arm and Sickles’ leg, none of the burial plots for these extremities have been documented. It would appear that these burial sites were not routinely marked and burial locations were not recorded in the hospital records. Although deliberate searches have been made for the burial sites of the amputated limbs, no such sites have yet been located except as mentioned at Richmond Hospital #18. Most sites of limb burial known today were incidentally discovered years later and no organized effort has been made to identify any bones found.

Take a closer look at amputation through the lens of a single story in this video

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this or donate to help preserve prosthetic limbs.

BECOME A MEMBER Arm and a Leg Campaign

References

- Barnes JK, ed The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion (1861-1865). Washington, DC: United States Printing Office; 1870-1888.

- Bollet AJ. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Tucson, AZ: Galen Press, Ltd.; 2002.

- MacLeod GHB. Notes on the Surgery of the War in the Crimea: With Remarks on the Treatment of Gunshot Wounds. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott; 1862.

- Garrison FH. The statistical lessons of the Crimean War. Military Surgeon. 1917; 40:457-473.

- Scrive G. A Medical-Chirurgical Account of the Crimean War, from the First Arrival of the Troops at Gallipoli to Their Departure from the Crimea. American Journal of Medical Science. 1861; 42(Oct):463-474.

- Fisher GJ. Report of Fifty-seven Cases of Amputations, in Hospital near Sharpsburg, Md. after the Battle of Antietam, September 17, 1862. American Journal of Medical Science. 1863;45(Jan):44-51.

- Stanley P. For Fear of Pain: British Surgery, 1790-1850. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Editions Rodopi, B.V.; 2003.

- Grattan W. Adventures with the Connaught Rangers, 1809-1814. London, UK: Longman; 1821.

- Abernathy BR, ed Private Elisha Stockwell, Jr., Sees the Civil War. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press; 1958.

- Bauer KJ, ed Soldiering: the Civil War Diary of Rice C. Bull, 123rd NY Infantry. New York, NY: Berkley Books; 1977.

- Benson SW, ed Confederate Scout-Sniper: The Civil War Diary of Berry Benson. Athens, GA: The University of Georgia Press; 1992.

- Blackford SL, Blackford CM, Blackford III CM. Letters from Lee’s Army. New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons; 1947.

- Bloomquist AK, Taylor RA. This Cruel War: The Civil War Letters of Grant & Malinda Taylor. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press; 2000.

- Davis WC, ed Diary of a Confederate Soldier: John S. Jackman of the Orphan Brigade. Columbia, SC: University of Sourth Carolina Press; 1990.

- 15.Dobson ASN. Conscripted: A Conflict of Conscience in Civil War Eastern Tennessee. St. Paul, MN: Tacitus Publications; 1997.

- Douglas HK. I Rode with Stonewall. New York, NY: Ballentine Books; 1940.

- Dreese MA. An Imperishable Fame: The Civil War Experience of George Fisher McFarland. Mifflintown, PA: Juniata County Historical Society; 1997.

- Duncan R, ed Blue-Eyed Child of Fortune: The Civil War Letters of Col. Robert Gould Shaw. New York, NY: Avon Books; 1992.

- Emery T. Richard Berwell: Thoroughbreds, Beagles, and the Civil War. Carlinville, IL: History in Print; 1997.

- Gerrish H. Letter to Lyman. Springfield, VA: Genelogical Books in Print; 1978.

- Hart AG. The Surgeon and the Hospital in the Civil War. Gaithersburg, MD: Olde Soldier Books, Inc.; 1987.

- Holland K, ed Keep All of My Letters: The Civil War Letters of Richard Henry Brooks, 5th Georgia Infantry. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press; 2003.

- Holmes Jr. OW. Touched with Fire: Civil War Letters of Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. 1861-1864.

- Holt D. A Surgeon’s Civil War. Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press; 1994.

- Hughes Jr. NC, ed The Civil War Memoir of Philip Daingerfield Stephenson, D.D. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press; 1995.

- Johnson PD, ed Under the Southern Cross: Soldier’s Life with Gordon Bradwell and the Army of Northern Virginia. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press; 1979.

- Keen WW. Military Surgery in 1861 and 1918. Ann Am Acad Political & Soc Science. 1918;80:11-22.

- Kostyal KM, ed Field of Battle: The Civil War Letters of Major Thomas J. Halsey. Washington, DC: The National Geographic Society; 1996.

- Lord W, ed The Freemantle Diary (The South at War). New York, NY: Capricorn Books; 1954.

- Lowe JC, Hodges S, eds. Letters to Amanda. Macon, GA: Macon University Press; 1998.

- McCrae M, Bradford M, eds. No Place for Little Boys. Brewer, ME: Goddess Publications; 1997.

- Menge WS, Shimrak JA, eds. The Civil War Notebook of Daniel Chisholm. New York, NY: Ballentine Books; 1989.

- Nevins A, ed A Diary of Battle: The Personal Journal of Colonel Charles S. Wainwright 1861-1865. New York, NY: DeCapo Press; 1962.

- Noe KW, ed The Memoirs of Marcus Woodcock, 9th Kentucky Infantry (USA). Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press; 1996.

- Olcott M, Lear D. The Civil War Letters of Lewis Bissell: A Curriculum. Washington, DC: The Field School Educastional Foundation Press; 1981.

- Olsen BA, ed Upon This Tented Field. Red Bank, NJ: Historic Projects, Inc.; 1993.

- Poe C. True Tales of the South at War: How Soldiers Fought and Families Lived, 1861-1865. New York, NY: Dover Publications; 1995.

- Ray JP, ed The Diary of a Dead Man 1862-1864: Diary & Letters of Ira Pettit. New York, NY: Eastern Acorn Press; 1981.

- Reeder J, ed From a True Soldier and Son: The Civil War Letters of C. H. Reeder. Brandy Station, VA: The Brandy Station Foundation; 1981.

- Rhodes RH, ed All for the Union: War Diary and Letters of Elisha Hunt Rhodes. New York, NY: Vantage Books/Random House; 1985.

- Robertson Jr JI. The Civil War: Tenting Tonight: The Soldier’s Life. Alexandria, VA: Time-Life Books, Inc.; 1984.

- Roy A. Memoir of a Civil War Casualty. Montgomery, AL: Elliot & Clark, Pub.; 1996.

- Saunders L. Ever True: A Union Private to His Wife: Civil War Letters of Private Charles McDowell, New York Ninth Heavy Artillery. Westminster, MD: Heritage Books; 2004.

- Sessareggo A, ed Letters from Home. Gettysburg, PA: Garden Spot Gifts, Inc; 2000.

- Sneden RK. Eye of the Storm: A Civil War Odessey. New York, NY: The Free Press; 2000.

- Styple WB, ed Writing and Fighting the Civil War: Soldier Correspondence of the New York Sunday Mercury. Kearney, NJ: Belle Grove Publishing Co.; 2000.

- Swank W, ed Confederate Letters and Diaries, 1861-1865. Shippensburg, PA: White Mane Publishing Co.; 1988.

- Swinn Jr CW, ed Letters to Lanah: A Series of Civil War Letters Written by Samuel Ensmenger, A Drafted Soldier. Gettysburg, PA: Clarence W. Swinn, Jr.; 1986.

- Tappert A, ed The Brothers’ War: Civil War Letters to Their Loved Ones from the Blue and Gray. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 1988.

- Toalson J, ed No Soap, No Pay, Diarrhea, Dysentery, & Desertion: A Composite Diary of the Last 16 Months of the Confederacy from 1864-1865. Lincoln, NE: Universes, Inc; 2006.

- Trimble R, ed Brothers ‘Til Death: The Civil War Letters of William, Thomas, and Maggie Jones, 1861-1865. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press; 2000.

- Woodward JJ, ed Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office; 1870.

- Berlin JV. A Confederate Nurse: The Diary of Ada W. Bacot 1860-1863. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press; 1994.

- Brinton JH. Personal Memoirs of John H. Brinton, Civil War Surgeon, 1861-1865. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press; 1996.

- Livermore M. My Story of the War: A Woman’s Narrative of Four Years of Personal Experience. New York, NY: Arno Press; 1972.

- MacCaskill L, Novak D. Ladies on the Field: Two Civil War Nurses from Maine on the Battlefields of Virginia. Livermore, ME: Signal Tree Publications; 1996.

- Billings JD. Hardtack and Coffee: Soldiers Life in the Civil War. Old Saybrook, CT: Konecky & Konecky; 1887.

- Bobrick B. Testament. A Soldier’s Story of the Civil War. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2003.

- Herdegen L, Murphy S, eds. Four Years with the Iron Brigade: The Civil War Journal of William Ray, Company F, Seventh Wisconsin Volunteers. New York, NY: Da Capo; 2002.

- Mayhue JT. A Civil War Journey: The Letters of John W. Brendel, 11th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regiment. Hagerstown, MD: Justin T. Mayhue; 2006.

- Morrow Jr. RF. 77th New York Volunteers: “Sojering” in the VI Corps. Shipensburg, PA: White Mane Books; 2004.

- Peltrie SJ. Bloody Path to the Shenandoah: Fighting with the Union VI Corps in the American Civil War. Shippensburg, PA: Burd Street Press; 2004.

- Smith AW. Reminiscences of an Army Nurse during the Civil War. New York, NY: Greaves Publishing Company; 1911.

- Patterson GA. Debris of Battle: The Wounded of Gettysburg. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books; 1997.

- Raus Jr. EJ. Ministering Angel: The Reminiscences of Harriet A. Dada, A Union Army Nurse in the Civil War. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications; 2004.

- Robson JS. How a One-Legged Rebel Lives: Reminiscenses of the Civil War. Gaithersburg, MD: Butternut Press; 1898.

- Sauers RA, ed The Civil War Story of Colonel Bolton, 51st Pennsylvania, April 20, 1861 – August 2, 1865. Coshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing; 2000.

- Schwartz G, ed A Woman Doctor’s Civil War: Esther Hill Hawks’ Diary. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press; 1984.

- Skidmore RS, ed The Civil War Journal of Billy Davis: From Hopewell, Indiana, to Port Republic, VA. Greencastle, IN: The Nugget Publishers; 1989.

- Straubing HD, ed In Hospital and Camp: The Civil War Through the Eyes of Its Doctors and Nurses. Stackpole Books: Harrisburg, PA; 1993.

- Whitehead WR. Adventures of an American Surgeon: A 19th Century Memoir. Bethesda, MD: Whitehead Books; 2002.

- Woolsey JS. Hospital Days: Reminiscence of a Civil War Nurse. Roseville, MN: Edinborough Press; 1996.

- Booth B. Dark Days of the Rebellion: Life in Southern Military Prisons. Garrison, IA: Meyer Publishing; 1996.

- Bodell DH. Montgomery White Sulphur Springs: A History of the Resort, Hospital, Cemeteries, Markers, and Monuments. Blacksburg, VA; 1993.

- Behling LL, ed Hospital Transports: A Memoir fof the Embarkation of the Sick and Wounded from the Peninsula of Virginia in the Summer of 1862. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press; 2006.

- Calcutt RB. Richmond’s Wartime Hospitals. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, Inc.; 2005.

- Atkinson JR. The Location of the “Clara Barton Hospital” at Antietam. Antietam, MD: James R. Atkinson; 1971.

- Dreese MA. The Hospital on Seminary Ridge at the Battle of Gettysburg. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers; 2002.

- Donald DH, ed Gone for a Soldier: The Civil War Memoirs of Private Alfred Bellard. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, & Co.; 1997.

- Moats MB. A History of Keedysville to 1890. Boonesboro, MD; 1890.

- Pfanz DD. War So Terrible. Richmond, VA: Page One History Publications; 2003.

- Taylor Jr LB. Ghosts of Williamsburg … and Nearby Environs. Williamsburg, VA: L. B. Taylor, Jr.; 1983.

- Ward E, ed Army Life in Virginia: The Civil War Letters of George C. Benedict. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books; 2002.

- Inge MT, ed Company Aytch: Or a Side Show of the Big Show and the Sketches of Sam Watkins. Middlesex, UK: Plume; Penguin Books; 1999.

- Whitman W. Memoranda during the Civil War. Bedford, MA: Applewood Books; 1993.

- McGrath T. Sherpherdstown: Last Act of the Antietam Campaign. September 19-20, 1862. Lynchburg, VA: Schroeder Publications; 2007.

- Cunningham HH. Field Medical Services at the Battles of Manassas (Bull Run). Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press; 1979.

- Alleman TP. At Gettysburg or What a Girl Saw and Heard at the Battle. A True Narrative. New York, NY: W. Lake Borland; 1889.

- Coco GD. A Vast Sea of Misery: A History and Guide to the Union and Confederate Field Hospitals at Gettysburg, July 1 – November 20, 1863. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications; 1988.

- Phares JLW. The Diary of John Louis Whitaker Pares, Company K, 16th Mississippi Infantry, Part I. Dallas Morning News. 1927 (Aug 28, 1927). http://mississippiconfederate.wordpress.com/2011/06/15/the-diary-of-john-louis-whitaker.

- Woolf L. Beyond the Arm. Cooperative Line. 2005. http://www.co-operative/issues/2005/october%202005/cover.htm.

- Koontz H, ed A Sanctuary for the Wounded: The Civil War Hospital at Christ Lutheran Church, Gettysburg. Gettysburg, PA: Christ Evangelical Lutheran Church; 2009.

- Ernst KA. Too Afraid to Cry: Maryland Civilians in the Antietam Campaign. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books; 1999.

- War Relics. The News, Frederick, Maryland. May 10, 1887.

- Coco GA. A Strange and Blighted Land: Gettysburg the Aftermath of Battle. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications; 1995.

- WaiteJr. RW. Confederate Military Hospitals in Richmond. Richmond, VA: Richmond Civil War Centennial Committee; 1964.

- Eggleston L. Artifact Under Exam: Mumified Arm. Surgeon’s Call. 2012;17(1):11-12.

About the Author

Dr. Robert Slawson is a 1962 graduate of the University of Iowa School of Medicine. He spent eight years as a medical officer in the United States Army, and had training in Radiology and Radiation Oncology, ultimately serving as Director of Radiation Oncology at Walter Reed General Hospital. In 1971 he joined the faculty of the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore, MD, and remained there until his retirement in 1998, although he still has a faculty position and works there part-time. He is currently a Master Docent at the NMCWM in Frederick, MD. Dr. Slawson also is actively involved in researching new topics on Civil War medicine and life in the nineteenth century. He has presented and published on several topics both for the Museum and for articles in other publications. He has had a book published on African American physicians in the Civil War: Prologue to Change” African American Physicians in the Civil War Era. Dr. Slawson is a member of the NMCWM and the Society of Civil War Surgeons.