The Incredible Dorence Atwater Story

Thomas P. Lowry

Originally published in Special Edition 2016 in the Surgeon’s Call

Few Civil War stories can match the heights and depths, the sorrows and triumphs, the abuses and rescues, of a Connecticut soldier, Dorence Atwater. And a principal rescuer was Clara Barton herself. Without her help, he would have died in a Federal prison for a crime he did not commit; with her help, he married a Tahitian princess and became wealthy and respected.

Atwater was from Terryville, CT, and served in the 2nd New York Cavalry beginning in August 1861. His regiment fought in many battles over the next two years. As Confederate General Robert E. Lee was invading Pennsylvania, headed for Gettysburg, Atwater was a courier. Near Hagerstown, MD, two Confederate soldiers, dressed in Union blue, captured him and shipped him to Belle Isle Prison, near Richmond, VA. Rebel prisons would be his life for the next two years.

“Belle” was hardly the word for this hell. In the humid heat of summer, it stank of raw sewage; in the winter, men lost feet to frostbite or simply froze to death. Confederate officers stole food sent by families in the north. Atwater was saved by a transfer to an indoor prison, where his fine penmanship and pre-war clerking experience won him a job keeping records. In February 1864, a quirk of administrative fate put him on a train to Andersonville, GA. That well-documented facility has won an ignoble fame, with its total lack of shelter, starvation rations of unfit food, and water supply contaminated by garbage and feces even before it entered the camp.

Clara Barton and Dorence Atwater.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The “hospital” was two acres of bare dirt. Medicine was scarce and even the Confederate inspectors found half the doctors to be “incompetent.” Most men admitted to this facility ended in the graveyard. For Atwater it was salvation. Somehow, his fine penmanship called him to the attention of Surgeon Isaiah H. White, who gave this young prisoner the task of keeping the death list. This was no easy task; Union men were dying at the rate of fifty a day. For each corpse, he recorded last name, first initial, regiment, company, and grave site location. One every six minutes. But he had to make a note every three minutes, because he was keeping a second list, a secret duplicate list, which he hid in his coat lining. Every night when he was returned to the hell of the main camp (his clerical work carried no perks), he concealed this list from the guards.

In September 1864, the approach of Union General William T. Sherman’s army alarmed the Confederate authorities, They quickly shipped thousands of prisoners north. Atwater and 12,000 other men soon found themselves at Florence, SC, in a stockade, once again destitute of shelter, where they quickly dug themselves new gopher holes. It is now the graveyard of 2,800 men who died from such hospitality. On February 27, 1865, at Wilmington, NC, Atwater and thousands of other prisoners were handed over to Union authorities. One ordeal was over; another was about to begin.

While Atwater was in service, his mother died. When he arrived home, his father was dying. Atwater spent his own money for medicine and doctors, but to no avail. In early April, his father, too, was dead. Two vital people were gone; three more were about to enter his life: Clara Barton, Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson, and Capt. James M. Moore.

Clara Barton’s life is well documented. Wilson commanded the forces that captured the Andersonville site, including the death list that Dr. White knew about. Barton had both the credentials and charm to get things done in politics. And she had seen the list that Atwater had smuggled north, past both his Confederate captors and his soon-to-be Union captors. At Barton’s request, Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered an expedition to Andersonville to mark the graves. This group was headed by Capt. Moore. He was ordered to take Barton and Atwater with him. Others in the group included three dozen clerks, laborers, and letterers. The shattered Southern economy slowed their trip. The Georgia rail connection moved at two miles per hour. The group, and a large shipment of boards and paint, arrived in early July. A month later, 12,000 graves had been marked, and the group started home.

The general tone of Atwater’s life was foreshadowed at Andersonville. Capt. Moore forbade both Atwater (the only member of the party who had ever been a prisoner) and Barton (who had set the expedition in motion) from any participation in the marking project. Further, in his final report, Moore mentioned only his own name and that of a letterer who had died of typhoid fever. No mention of Atwater, Barton, or any of the workers and soldiers who died completing the project. Now began the era in Atwater’s life which might be called The Game of Lists.

The secret list that Atwater smuggled for so long we will call the “Hidden Copy.” The list that Wilson’s troops seized at Andersonville, we will call the “Wilson List.” (The Wilson list had 2,200 fewer names than the Hidden Copy.) While the records are confused, it appears that there was a third list, a copy of the Hidden Copy, which the War Department termed the “Original Copy.” A messenger from the War Department came to Andersonville during the grave-marking process and seized the Original Copy and took it away. It appears that Atwater retained his Hidden Copy, perhaps concealing it from the authorities.

Belle Isle Prison Camp, Virginia.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

If this were a movie, the sound track music would shift into a minor key, an ominous key. Keep in mind that all 12,000 graves had been marked, with name and regiment; but the families of those 12,000 men had no idea of their fate. The War Department, even with access to at least two lists, had no intention of publishing the list(s) or of notifying the families of the dead. It is also vital to note that Atwater’s enlistment had run out and he was no longer in the army.

Atwater, a combat and prison veteran, knew the soldier’s military mind. Now he was to meet the bureaucratic military mind, the mind of the paper-shuffler, the nit-picker, the obstructionist, or in Freudian terms, the anal-retentive. There were two such who dogged him, even beyond the grave. The first was Col. Samuel Breck, an Assistant Adjutant General. The other was Col. Edward D. Townsend, who had been an army bureaucrat for many decades. (He graduated from West Point twelve years before Atwater was born.)

When Atwater was freed from POW camp, he was deposited at Parole Camp. He wanted to go home and see his father, but could not get a furlough, because he was no longer in the army. Having slipped out of the paper-work noose, he went home and came down with near-fatal diphtheria, lying sick next to his dying father. Soon the father was dead; and his son had his first encounter with Breck and Townsend, whose dogged fury matched that of Inspector Javert who hounded Jean Valjean in Victor Hugo’s classic Les Miserables. In late March 1865, Breck sent telegrams to both the commander of Parole Camp and the military police near Atwater’s home, to seize the ailing, grieving young man and “send him to this office at once bringing the list of soldiers who died in the Rebel prison now in his possession.” Presumably, Breck had possession of both the “Original Copy” and the “Wilson Copy.” Somehow Breck had determined that Atwater still had his “Hidden Copy,” the one he smuggled for months, hidden in his coat lining. What Breck desired was possession and total control of every single copy of the Andersonville dead list.

In mid-April, Breck telegraphed the ailing Atwater directly, ordering him to come from Connecticut to Washington, DC, and bring the “Hidden List.” He complied the next day. Upon arriving, he found Breck was away, and left the list with Breck’s chief clerk. Now Breck had possession of every copy. The next day, he returned and told Atwater that Stanton had authorized $300 to buy the rolls. The young man replied that he did not wish to sell them, that he wished to publish them for the benefit of the families of the dead. With no bargaining chip left, Atwater finally agreed to these terms: He would re-enlist in the General Services corps, receive a clerkship in the War Department, the $300, and get his (“Hidden”) list back after Breck’s staff had copied it. (Hand copied, of course. No Xerox machines in 1865.)

The confusion of lists gets more opaque. The copy of what Atwater had delivered is now referred to as the “Breck List” and is probably identical with the “Original Copy.” For several months, Atwater made inquiry as to when he would get back his copy. In August, Breck told him that he could have the list if he repaid the $300. But Atwater had spent the money on his father’s medical and burial expenses. Breck then accused Atwater of “setting himself in business.” When the young clerk protested, Breck had him arrested, put in the guard house, and then transferred to Old Capitol Prison. At a court-martial a few days later, Atwater was charged with conduct prejudicial to good order and military disciple and with grand larceny. The trial transcript is dizzying in its contradictions, confusions, and probable perjury. The gist of the proceedings is this: the prosecution asserted that Atwater had never been entitled to any of the lists at any time, even the one he had hidden in his coat lining while a prisoner in Andersonville. He was found guilty of both charges and sentenced to a dishonorable discharge, eighteen months at hard labor, and the requirement that he repay the $300 before he could be released. How he was supposed to raise $300 ($9,000 in today’s money) while locked up remains unknown.

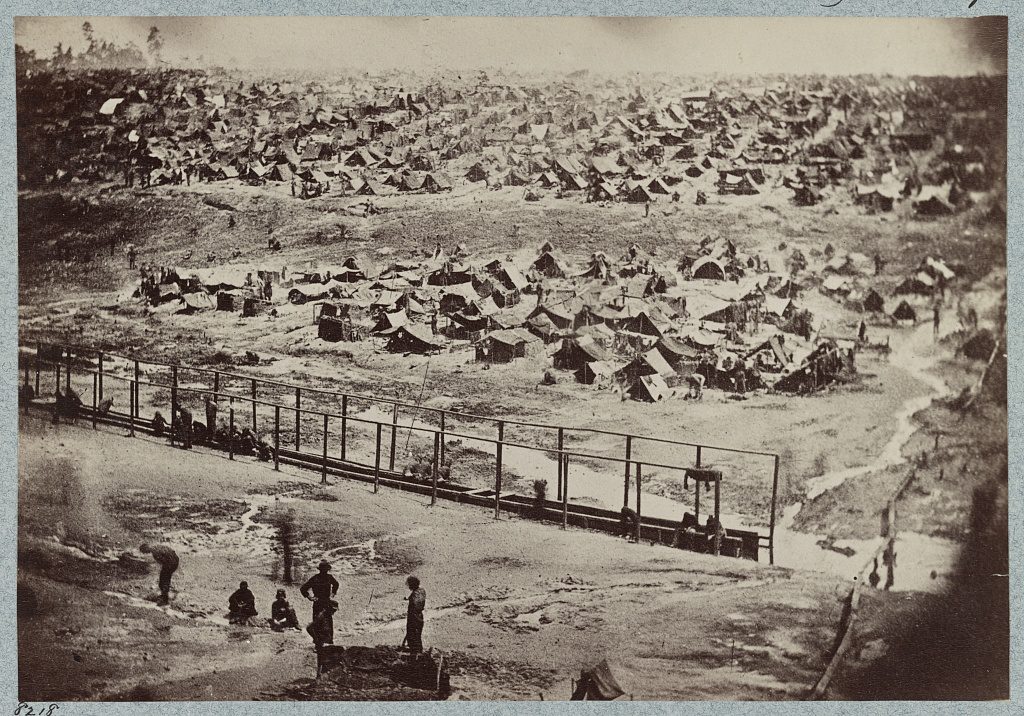

View of Andersonville Prison, August 1864.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

Eighteen months at hard labor while still recovering from two illnesses and two years of severe malnutrition– a strange reward for dedicated service. Starved by the Confederacy and now a felon locked up by the United States of America, the nation he fought to preserve. Worse, the War Department had no intention whatsoever of publishing the lists, any of the lists. Compassion, common decency, and regard for widows and orphans played no part in the mind of the bureaucrat. Could there be a silver lining in this black cloud, breaking rocks in New York’s Auburn Prison while shivering with malaria, with throat still raw from diphtheria?

Happily, there were not one but two silver linings. Atwater had a list, possibly the Breck list, hidden somewhere. Even facing severe threats, he refused to disclose its location. Breck had Atwater’s home and hotel room searched, but to no avail. The second silver lining was that Atwater had friends. And in Washington, DC, then as now, having the right friends meant everything.

Prominent among those friends were Clara Barton, Maj. Gen. Benjamin Butler (the consummate insider), Horace Greeley (editor of the influential New York Tribune) and a host of angry Connecticut politicians. After two months in prison, Stanton released Atwater. He was not pardoned. His verdict was not overturned. He was just – out. His release was not popular with Breck or Col. Townsend. The latter objected strongly, claiming that “Such an act of clemency … would give a coloring to his (Atwater’s) false representations against the Adjutant General’s office.”

While paper-pushers fumed, Atwater brought his long-concealed list to Horace Greeley, who set his type setters to work. Two months later, in January 1866, the Tribune published a special edition, more like a thick book, of all 12,000 Andersonville dead, with their ranks, companies, and regiments. There were introductory essays by Atwater himself and by Clara Barton, whose words are well-worth quoting.

“For your record of the dead, you are indebted to the forethought, courage, and perseverance of Dorence Atwater, a young man not yet twenty-one years of age; an orphan; four years a soldier; one-tenth part of his life a prisoner, with broken health and ruined hopes, he seeks to present to your acceptance the sad gift he has in store for you; and, grateful for the opportunity, I hasten to place beside it this humble report, whose only merit is its truthfulness, and beg you to accept it in the spirit of kindness in which it is offered.”

Contrary to Breck’s assertion that Atwater was “setting himself up in business,” he received not one cent for his list. Greeley published the list at cost, twenty-five cents a copy. It sold out immediately. Now Atwater, his mission accomplished, set out to clear his name.

In March 1866 he sent a detailed memorial to Congress. Rep. Robert S. Hale had this comment, “…it is impossible for any intelligent man to read the record of that court-martial without saying it is a case of the grossest and most monstrous cruelty and injustice that ever oppressed any human being.” Hale sent the case to President Andrew Johnson, who sent it on to the Judge Advocate General, Joseph Holt, whose legal opinion is a masterpiece of convoluted analysis, couched entirely in the passive voice. In plain English – “pardon Atwater.” Adjutant General Townsend objected to a pardon, saying that a pardon “would give a coloring to Atwater’s false representations against the Adjutant General’s office.” The president passed the buck to Stanton – who did nothing.

Andersonville Prison Cemetery, August 17, 1865, Clara Barton raising the flag.

From Harper’s Weekly, October 7, 1865, Courtesy of the Library of Congress

This was the era before civil service. Federal jobs were awarded for political reasons. Here this system worked for Atwater. Letters and behind-the-scenes pressure from Clara Barton, the governor of Connecticut, and many Congressmen resulted in Atwater being appointed U.S. Consul for the Seychelles, an 800-mile arc of tiny islands off the coast of Madagascar. There he took up his new post at the capital, Mahé. His duties were not onerous – in a typical year only four American ships put in at Mahé. In 1870, after several complaints about Atwater, the Seychelles consul post was scheduled to be closed. Again Clara Barton came to his defense, and the governor of Connecticut suggested a post in the Bahamas. Many internal documents are missing, but in 1871 Atwater became U.S. Consul for the Society Islands, better known as Tahiti. Now his life took a totally new direction. He was age twenty-six.

Until his death in 1910, his life centered around Tahiti. He became the owner of a number of trading vessels and pearl fisheries. He owned twenty-five acres of vanilla trees. After only four years in his new home, he married a princess of the royal Tahitian family, Moetia Salmon. With his friend, Robert Louis Stevenson, then America’s best-known author, he established a steamship line. He often traveled to San Francisco, CA, where he had many friends. Upon his death he had a state funeral at Papeete, fully documented in photographs.

Even in death, his legacy was debated by civilian supporters and military bureaucratic detractors. His widow, whose holdings were destroyed during the 1914 bombardment by the German navy, was long-delayed in receiving a widow’s pension, by four years of shameless obfuscations by the Pension Bureau.

Clara Barton, thirty years after the war, came once again to Atwater’s defense. At a Connecticut celebration, she again denounced his still-extant record of dishonorable discharge. Clara Barton and Dorence Atwater — two American heroes.

Sources

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, Record Group 153, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General: file MM2766 (Atwater trial)

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, Record Group 153, Records of the Office of the Judge Advocate General: file MM2975, eight boxes (Wirz trial).

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, Record Group 59, General Records of the Department of State, NARS A-1, Entry 778,Vol. 6 of 12, 250/48/02/01.

National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC, Civil War Pension file (widow) 1,061,830.

About the Author

Thomas P. Lowry, A native Californian, graduated from Stanford Medical School in 1957. After forty years of medical work, he has dedicated his remaining years to history research and writing, and is author of twenty-five non-fiction history books. His book on Lewis and Clark earned him a Meritorious Achievement Award. He is married to Beverly Lowry, his co-author of a database of 80,000 Civil War courts-martial. They have four children and six grandchildren.