“Necessary Hygienic Conditions” – Civil War Sewers

One of our most commonly asked questions is “Where did all those soldiers go to the bathroom?” The story of Civil War sanitation and sewage in hospitals is not often told, but one that should not be neglected.

By the end of 1864, the Union Army had constructed 187 pavilion hospitals for long term care as well as a number of temporary hospitals, which were established in existing facilities such as churches, hotels, and schools. The Confederates had similar arrangements. Pavilion hospitals comprised individual rectangular, one-story wards interconnected by long corridors or covered walkways. The wards were self-contained to minimize the spread of disease. An essential aspect of army hospitals was to supply each ward with water, preferably both hot and cold, for drinking, bathing, and wound care. The water supplied to the hospitals also served the vital function of helping collect and dispose of bodily wastes.

Detail of Ward Pavilion, Satterlee Hospital

(a) = patient bed space (b) = wardmaster’s room (e) bath room with tubs

(c) = nurse’s room (d) = water-closets (toilets) and wash basins

Dr. William Hammond, then the Surgeon General of the Union Army, set forth the basic principles of sanitation 1863. He recommended one bathtub for every 26 patients, one water-closet, or toilet, for every ten and one wash basin for every ten. Ventilation of the toilet area was stressed as very important, and, if water was available, it was to carry off fecal material immediately.

Many hospitals came close to or fully achieved these ideal suggested conditions. However, in some cases the water supply was insufficient to permit continuous flow through the toilets, so they were flushed only every few hours or so. Similarly, some hospitals utilized privies (outhouses) for waste collection in an outdoor pit or box which had to be emptied periodically. All went to great lengths to adequately ventilate the water-closets. These issues were especially hard to address in the temporary hospitals, since they were often not easy to modify to meet the standards. When multi-story buildings were used it was sometimes necessary to provide running water to only a few lower stories and carry water in buckets to the higher floors.

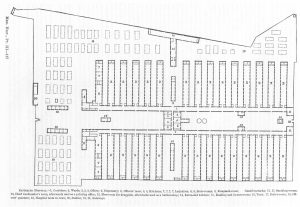

Let’s look at a specific example. The figure below shows Satterlee Hospital, a typical pavilion style hospital ward in West Philadelphia. Similar plans were utilized with minor variations throughout the hospital system. The plan shown was designed for 48 patients to be housed in the ward, which was 167 feet long by 24 feet wide. Overall, Satterlee had 3,519 beds in 44 wards of varying lengths.

Plan of Satterlee Hospital in West Philadelphia. Each ward (labeled #2) had a water closet and bath room at the far end.

On the left end of the figure, the ward is connected to the rest of the hospital, in this case by a corridor which leads to other parallel pavilions. The far end of the ward held the toilet and washing facilities, separated from the patients by a narrow corridor.

The bath room had a cast iron tray with hot and cold water pipes running above. The wash basins were placed in the tray, and waste water ran down the tray into a drain pipe. A cast iron bathtub with hot and cold water was also in the room. Hot water was steam heated in the kitchens and distributed to the wards in iron pipes. There was only one tub for 48 patients, while the hospital standard would have recommended three, one for every 16 patients. In the water closet room, a 12 foot long cast iron trough was placed under toilet seats. A constant flow of water carried waste matter into a sewer line.

Satterlee was fortunate to have a municipal water supply and sewerage system available. Many hospitals had to pump water from rivers, creeks, or ponds and then discharge their waste water into holding tanks, cesspools, or even the supply from whence is came. At Camp Dennison Hospital in Ohio, the waste water was discharged in the supply river upstream from the intake point, a highly undesirable practice.

Despite the difficulties, only a minute percentage of cases on record where faulty ventilation of sewerage could be blamed as the cause of disease outbreak. It is not known how many cases of disease, if any, were spread due to hospital water supply systems. Considering the overall mortality rate of the hospitals, which was only eight percent, it is safe to assume that water supply sanitation was not a major problem.

The text of this post can be found in all the restrooms at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine.

Tags: Civil War, Civil War Hospitals, Civil War Medicine, Civil War sanitation, Satterlee, William Hammond Posted in: Uncategorized