After the Amputation

Help us preserve some of the prosthetic limbs in our collection by supporting our “Arm and a Leg Campaign”

At the Battle of Ox Hill on August 31, 1862, Walter Lenoir, a thirty-nine-year-old North Carolinian was struck by a Minié ball in the right leg. As he lay writhing in the dirt, his mangled leg leaking blood into the grass and bullets spraying the soil around him, his mind filled with the thoughts of things his disability would deprive him of. “First I thought of my favorite sport of trout fishing, which I would have to give up. Then I thought of skating, swimming, and partridge hunting,” Lenoir wrote afterwards. Yet, these activities did not occupy his foremost thoughts. Instead, Lenoir confided: “before all these things I thought sadly of women; for I was not old enough to have given up the thought of women.”[1] Lenoir was justifiably afraid that his injury would leave him crippled, unloved, and alone. His fear was justifiable—Lenoir lived in a culture that valued the whole body as a mark of manliness.

To Americans living in the late nineteenth century, disability could be a window into character. A limp or an amputation could be evidence of moral degeneration as well as physical harm. What would happen to men like Lenoir who returned from the war missing an arm or a leg? In part to help men like Lenoir, a flourishing prosthetics industry rose during the war to meet this need.

Field Day by R.B. Bontecou

Historians have estimated that just under 30,000 Union soldiers lost a limb during the war, with over 21,000 surviving the operation. The actual numbers were likely higher due to the fact that the Union did not bother to start keeping track until the second year of the war. We don’t know the numbers of Confederate amputations because the medical records went up in flames as the Davis administration fled Richmond in terror of Grant’s Army in 1865.

Prosthetics were obviously important for mobility, but they were also important for amputees to become inconspicuous in civilian society. Numerous Americans wondered during the war what would happen to amputees when they returned home, how would they blend in? “At an age when appearances are reality,” wrote Oliver Wendell Holmes in 1863. “It becomes important to provide the cripple with a limb which shall be presentable in polite society, where misfortunes of a certain obtrusiveness may be pitied, but are never tolerated under the chandeliers.”[2] The federal government subsidized artificial limbs for documented Union soldiers who suffered an amputation. Washington would provide an artificial limb or a financial commutation of up to seventy-five dollars. Because they had engaged in rebellion, Confederate veterans were not eligible for federal subsidies for artificial limbs. Some former Confederate states like North Carolina and Virginia funded their own artificial limb programs to provide old Johnny Rebs with their own prosthetic legs.

As Laurann Figg and Jane Farrell-Beck have shown, the Civil War was a boon for the prosthetic limb industry. Between 1845 and 1861, 34 patents were issued for prosthetic limbs, while between 1861 and 1873, 133 patents were issued for prosthetic limbs.[3]

As Laurann Figg and Jane Farrell-Beck have shown, the Civil War was a boon for the prosthetic limb industry. Between 1845 and 1861, 34 patents were issued for prosthetic limbs, while between 1861 and 1873, 133 patents were issued for prosthetic limbs.[3]

Many Americans were awed by the advancement in artificial limb technology, often praising the craftsmanship of the manufacturers, such as George Jewett, James Edward Hanger, D. DeForrest Douglass, Benjamin Franklin Palmer, and Douglas Bly. One newspaper praised the Douglass artificial limb, exalting the realism of the prosthetic: “it is difficult to distinguish the artificial member from genuine flesh and blood.”[4] They were designed to be inconspicuous, so that the wearer could blend into society without strangers knowing that he was an amputee. Adelaide Smith remembered that when she was working as a nurse during the war, many amputees were being supplied with artificial limbs. She was surprised “how many were well fitted with these limbs” and “could walk so well that only a slight limp betrayed them.”[5]

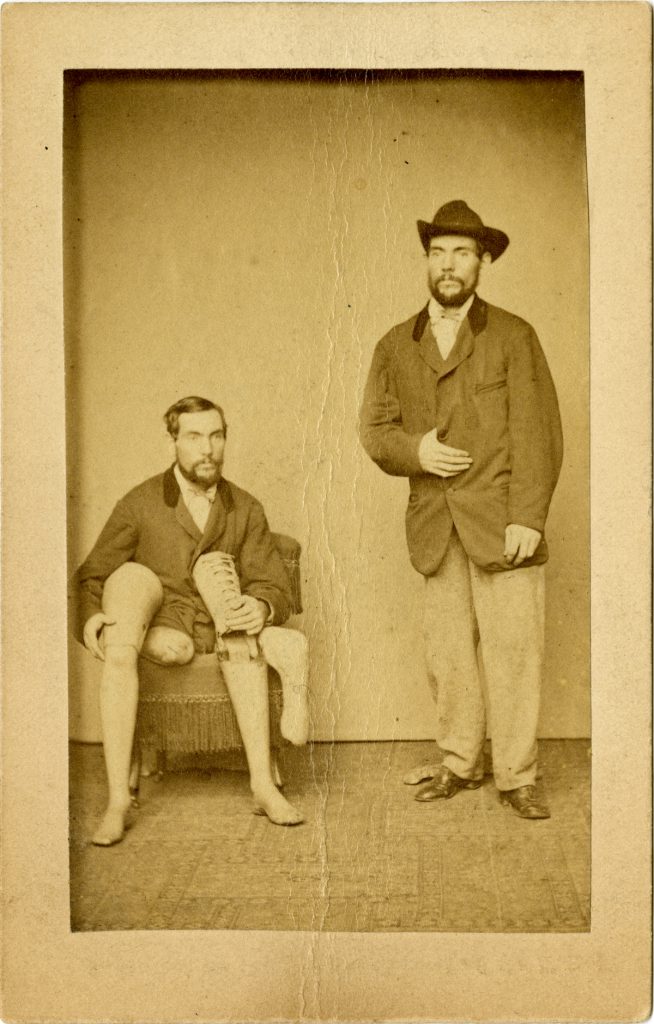

A. A. Marks advertising card, showing a customer holding and wearing his artificial legs, late 1800s

Courtesy Warshaw Collection, Archives Center, National Museum of American History

However, prosthetic limbs were not always the successes that Adelaide remembered them to be. Many Civil War amputees recalled that the physical rehabilitation was trying. Most expected (often because of advertisements of the prosthetic limb industry) that they would be able to strap into their new leg and walk as normally as they did before the injury. Yet, they often found that they needed to re-learn how to walk with a prosthetic limb. Napoleon Perkins was a New Hampshire native who fought with the Fifth Maine Artillery and had his leg shot off at the Battle of Chancellorsville in 1863. Following his amputation, Perkins was transferred to Stanton Hospital in Washington, D.C., where he was measured and fitted with a Jewett leg. When he first strapped into his Jewett leg, he was “expecting to be able to walk at once” but was disappointed that he “could hardly walk with the aid of my crutches.” He returned to his cot “feeling rather blue” but not defeated. After repeated tries, Perkins finally learned to walk without aid on his prosthetic limb. “Shall always remember the first step I took without help,” he wrote. “Felt as proud as a little child learning to walk.”[6]

Prosthetics solved the problem of mobility for many, though not all, Civil War veterans. Prosthetics, however, had limitations. For veterans with an arm amputation, no inconspicuous prosthetic existed. The best options were prosthetic arms with hooks, and many veterans with a missing arm preferred an empty sleeve to a metal hook. Moreover, prosthetic limbs could not fix the emotional and psychological damage of amputation.

Many disabled Civil War veterans felt embarrassed and shamed of their disability, and even a prosthetic limb could not fill the deep void an amputated limb could leave. Following his discharge, Napoleon Perkins returned to Lebanon, New Hampshire—his hometown. But his disability left him with a gnawing feeling of inferiority that he could not shake. “My crippled condition I felt very keenly,” Perkins wrote in his memoir in the early twentieth century, “and as for that matter, I never entirely got past that feeling.”[7]

Learn More in this interview with historian Moyra Williams Schauffler about her research on prosthetic limbs

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this or donate to help preserve prosthetic limbs.

BECOME A MEMBER Arm and a Leg Campaign

About the Author

Dillon Carroll received his PhD from the University of Georgia in 2016 where he had studied with Dr. Stephen Berry. He currently lives in New York City where he teaches courses in American history, the Atlantic World, Gender and Sexuality and the History of Medicine at Hunter College and St. Francis College. In addition to teaching, researching and writing, he spends his time trying to find the best happy hours in the city.

Footnotes

[1] Walter W. Lenoir Diary, Lenoir Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

[2] Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Human Wheel, Its Spokes and Felloes,” Atlantic Monthly, 1863, 574.

[3] Laurann Figg and Jane Farrell-Beck, “Amputation in the Civil War: Physical and Social Dimensions,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 48 (1993): 456-463.

[4] The News-Herald (Hillsboro, Ohio), 9 February 1888.

[5] Adelaide W. Smith, Remembrances of an Army Nurse During the Civil War (New York: Greaves Publishing Company, 1911), 189.

[6] Napoleon B. Perkins, The Memoirs of N.B. Perkins, 20, New Hampshire Historical Society.

[7] Ibid.

Tags: Amputation, Amputee, Dillon Carroll, Mercy Street, Prosthetics, Season 2 Posted in: Mercy Street PBS