The Power of Place – How an Ordinary Space is Transformed with History

The power of place in history is undeniable. There are certain places where you can almost feel the weight of past events. In some areas it can be obvious where that feeling comes from – as on battlefields like Gettysburg. In others, you don’t feel the weight unless a good storyteller reveals how such an interesting place could be hiding in plain sight.

Knowing the history of a given place transforms a seemingly ordinary spot into something worthy of a pilgrimage. The beauty of history is that it’s literally everywhere. It’s the job of the historian to sensitize people to the history hiding in the places where they live, work, and play.

One of my favorite Civil War places is in Frederick, Maryland at the intersection of Record and 2nd Street. The intersection brings together so many of the elements at play during the Civil War.

The Presbyterian Church at the intersection of 2nd and Record. Built in 1825. Photo by author

After the Battle of Antietam, fought on September 17, 1862, 8,000 wounded soldiers were brought to Frederick, doubling its population nearly overnight. Wounded soldiers filled every large structure in town – churches, schools, hotels, private homes, and even a bowling alley. Two of the hospital sites are adjacent to the intersection of Record and 2nd. A Presbyterian Church (still standing) and what used to be the Frederick Academy (demolished in the 1930’s).

Soldiers wounded at the battle of Antietam were fortunate because for the first time there was a modern emergency evacuation system to ensure they all got to hospitals within 24 hours of the end of the battle (something that took up to a week in earlier battles). Their journey to Frederick wasn’t an easy one however. The wounded had to travel the bumpy 20 mile journey from the battlefield over a small mountain in a covered ambulance wagon train or by simply walking as best they could.

Though the amount of time it took to route over 8,000 men into hospitals feels slow to us, it represented a large step forward for emergency medicine that represented the beginning of innovations that today play out on national television in responding to mass casualty events.

The Ramsey House today. Photo by author

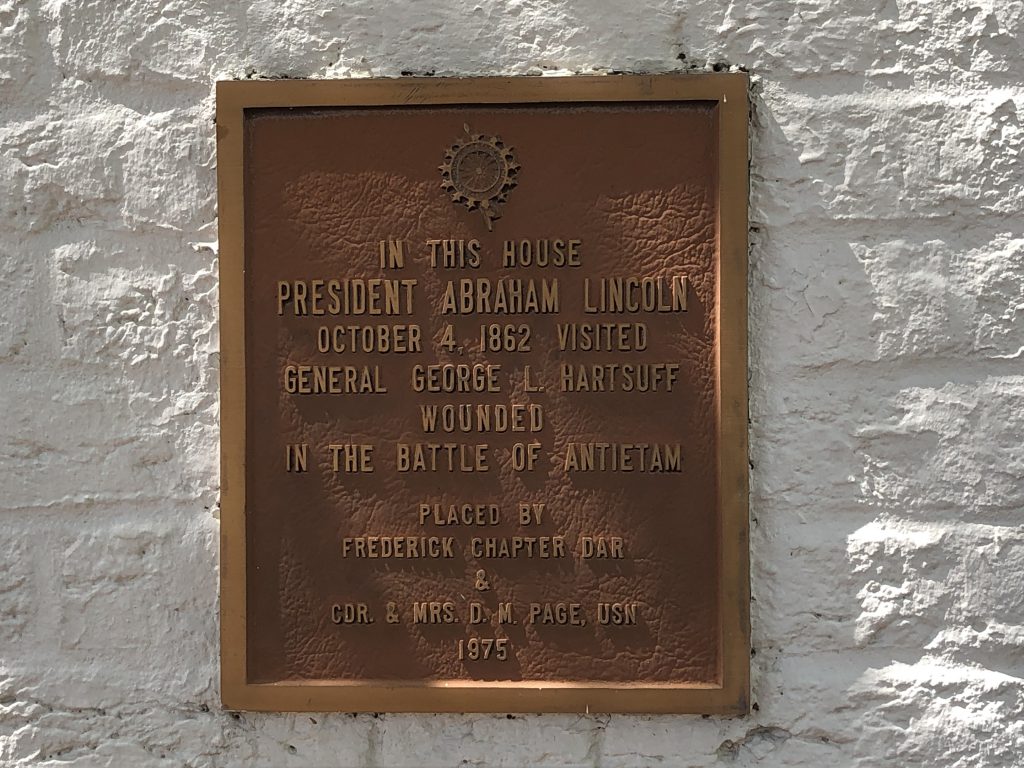

Also adjacent to the intersection was a home owned by Mrs. Ellen Ramsey, where Union General George L. Hartsuff spent time recovering from ghastly wounds sustained at Antietam. President Abraham Lincoln visited General Hartsuff on October 4, 1862 on his way back to Washington, DC from visiting the Army of the Potomac. Upon exiting the house, Lincoln was beset by a crowd of excited Frederick residents who begged to hear a speech from the exhausted president.

Lincoln proceeded to give one of the greatest non-speeches ever.

In my present position it is hardly proper for me to make speeches. Every word is so closely noted that it will not do to make trivial ones, and I cannot be expected to be prepared to make a matured one just now. If I were as I have been most of my life, I might perhaps, talk amusing to you for half an hour, and it wouldn’t hurt anybody; but as it is, I can only return my sincere thanks for the compliment paid our cause and our common country.

Plaque commemorating Lincoln’s visit. Photo by author.

Lincoln avoided serious public remarks, but satisfied the onlookers, giving them a chance to have heard presidential oratory. Charles Johnson, of the 9th New York who was recovering from his hip wound suffered at Burnside’s Bridge, in the nearby Presbyterian Church saw the episode play out and remarked on Lincoln’s increasingly careworn appearance:

Abraham Lincoln passed through the city today on his return from the review of the army on the upper Potomac. He paid the honor of a visit to a certain General who was wounded at Antietam and is stopping opposite here, and to the crowd which collected around the door and cheered him, he made a speech of his usual brevity. He was then assisted into an unpretentious one-horse buggy by a field officer who accompanied him. They passed the hospital, and I had an excellent view of the features of the President. He looked more worn than when I saw him last, and the heavy load he is obliged to carry, amply accounts for that. My present condition is not overly pleasant, but by far better than is his.

The last site worth noting adjacent to the intersection is a row of buildings next to where the Frederick Academy stood. They are some of the few remaining known slave quarters in Frederick. Even though slavery wasn’t a central component of the Frederick community the same way it was throughout much of the South, it was still a fixture. In 1860 more than 1,000 of Frederick’s 8,000 residents were African American split about equally between enslaved and free, and the still standing buildings provide a silent reminder of that past.

What drew the hospital sites and the slave quarters together in an unexpected way was the passage of the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. It made it the official war policy of the Federal army to free slaves as they encountered them. Even though that only applied to states “in rebellion” (therefore not applicable in Maryland) and didn’t ensure that slavery would one day end in border states like Maryland, it suggested a hopeful future where that might be the case.

Standing slave quarters on 2nd Street. The Presbyterian church is a bit further down and across the street. Photo by author.

The intersection of 2nd and Record, which was just another street corner at the beginning of September 1862, became a visual representation for all of the challenging dynamics brought about by the Civil War. Here wounded Union soldiers recovered a short distance from enslaved workers who wouldn’t be freed with a victory unless a more radical step was to follow the Emancipation Proclamation.

The day of Lincoln’s visit on October 4, 1862 brought a sitting president, a general, common soldiers, and enslaved African Americans together just days after the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation had been issued.

The corner of Record and 2nd streets in Frederick on October 4 foreshadowed the legacy of the Civil War. Surrounding the president were recovering soldiers who had been brought to Frederick through a modern emergency evacuation and triage system which had been first introduced at the Battle of Antietam and is still used by our society today.

Likewise, the Emancipation Proclamation marked the first step in making the end of slavery a Union war aim. While not universally approved in the North, it was an important beginning that paved the way for the 13th Amendment through the lens of military necessity.

Both the Emancipation Proclamation and the system of emergency medicine were new when Lincoln visited Frederick, but they represented the dawn of a coming age for the United State in terms of freedom and emergency medical care.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

John Lustrea is a member of the Education Department and the Website Manager at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He earned his Master’s degree in Public History from the University of South Carolina. Lustrea previously worked at Harpers Ferry National Historical Park during the summers of 2013-2016.

Tags: Abraham Lincoln, Civil War, Civil War Hospitals, Civil War Medicine, Downtown Frederick, Emancipation Proclamation, Frederick, Slavery Posted in: Uncategorized