Home from the War

In 1893, a disabled veteran in dire financial straits wrote to Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain to ask for a loan. “I am in bitter sorrow and distress,” William Wiegel wrote, “I have been sick from my old wounds for month and am just able to get about a little upon my crutches.” The veteran had taken out loans against his furniture to make ends meet, and his loans were coming due. “In this hour of sorrow and bitter trial, remembering your kindness of heart, and your generous Christian nature,” Wiegel wrote, “I come to you and beg you to please loan me $23 for a few months.”

Wiegel wasn’t the only Union veteran who wrote to a former commander or comrade looking for help in the years after the Civil War, and he certainly wasn’t the only one who struggled after leaving the army. Veterans, particularly those with disabilities, faced significant challenges in reintegrating into society, finding and keeping work, and maintaining personal relationships.

Work was one of the greatest challenges. Some disabled veterans found great career success after leaving the army – occasionally the combination of the cultural cache of an ‘empty sleeve’ and an adoring public sometimes helped propel particularly charismatic men into public service. However, many veterans simply could no longer perform the physically taxing work, like farming, that they had done before the war. For example, a recent study found that in one sample of Union veterans, there was a significant decrease in manual labor and significant increase in white collar jobs between the 1860 and 1870 census.[1] Of course, the choice to pursue a desk job was an option not open to all; some veterans attempted to keep working in their former trades, to varying degrees of success.

When it came to work, disabled veterans faced a complex set of problems. Most veterans wanted to continue to work, but faced discrimination and limited opportunities when they looked for jobs. Historian James Marten has suggested that former soldiers were treated with suspicion when they re-entered the job market – civilians worried that their reliance on the army for their food, clothing, and lodging had made them accustomed to being taken care of, or perhaps years of rough living had made them dangerous and immoral. Of course, disabled veterans were more problematic since it was often assumed they could not perform as well as an able-bodied employee.[2] To combat this preconception, disabled veterans went to great lengths to demonstrate their ability. One famous example was a series of left-handed penmanship contests offered by newspaperman William Oland Bourne, designed in part to prove that amputees could make good employees.

Nice penmanship or not, most disabled veterans required the support of the federal government in the form of a pension at some point in their post-war lives. The federal pension program, created in 1862 and updated periodically until 1907, defined disability as the inability to perform manual labor – meaning that in order to get what many soldiers believed was a fair payment, they had to swear that they could no longer work. Yet, late 19th century Americans believed that labor and masculinity were critically enmeshed; only women, children, people of color, and the unworthy poor were dependent on others for their survival. This put Civil War veterans – supposedly the best men America had to offer – in a difficult position: in order to get their pension, they needed to fashion themselves as utterly disabled, which meant risking their masculinity. But if they clung to their manhood, whether that meant continuing to work, reluctance to describe their suffering, or admit their reliance on others, they could be denied a pension.

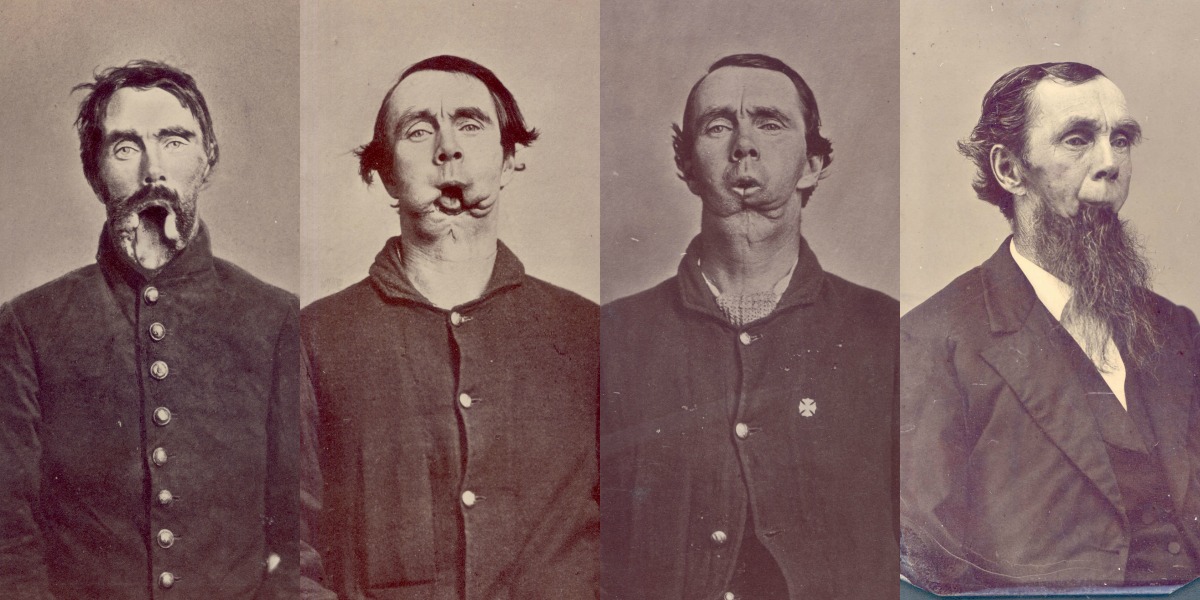

Some veterans found ways to create some gray area in this black-and-white system. Rowland Ward, whose facial wounds were photographed numerous times by the Army Medical Museum, testified to the Pension Bureau that he could not work, but his obituary describes him as a life-long farmer and newspaper reports show that he owned a substantial amount of property in western New York State.[3] Stories like Ward’s are an important reminder that the lives of disabled veterans were never simple – the fact that Ward still operated a farm doesn’t mean he wasn’t disabled. Either way, of course, it meant he needed to create a narrative of helplessness in order to earn the pension he believed he deserved.

Work was just one of the problems that disabled veterans encountered when they mustered out. Sometimes they used alcohol, even laudanum and opium, to help them cope with pain, frustration, and war trauma. Others lived in asylums. Many veterans struggled to reintegrate into their families, and those who failed lived away from home in soldier’s homes or became tramps. Others channeled their distress into violence toward their families, and in some cases, themselves, solving their problems permanently by choosing to die.

William Wiegel died a century or more ago, but elements of his pleas don’t seem too far removed from those echoed by today’s veterans: the need for health care, jobs, and access to system of support. One thing is certain: as long as we have war, we’ll have veterans in need.

About the Author

Sarah Handley-Cousins is a historian, teacher, and writer living in Buffalo, NY. She received a PhD in history from State University at New York at Buffalo in 2016. Her scholarly interests include medicine, gender, disability, and war studies. She is also an editor at Nursing Clio and producer of The History Buffs Podcast.

Footnotes

[1] Jalynn Olsen Padilla, “Army of Cripples: Northern Civil War Amputees, Disability, and Manhood in Victorian America,” PhD Diss, University of Delaware, 2007, 72.

[2] James Marten, Sing Not War: The Lives of Union & Confederate Veterans in Gilded Age America (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 55-58.

[3] “He Lived 36 Years Without a Jawbone,” New York World, July 3, 1898; Pension Case File of Rowland Ward, certificate number 47, 031

Tags: Amputation, Amputee, Mercy Street, Pension, Real to Reel, Reconstruction, Sarah Handley-Cousins, William Oland Bourne, William Wiegel Posted in: Uncategorized