Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr. and the Aftermath of Antietam

“In the dead of the night which closed upon the bloody field of Antietam, my household was startled from its slumbers by the loud summons of a telegraphic messenger,” wrote Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes in the opening of his essay in the December 1862 edition of The Atlantic.

“The air had been heavy all day with rumors of battle, and thousands and tens of thousands had walked the streets with throbbing hearts, in dread anticipation of the tidings any hour might bring.”

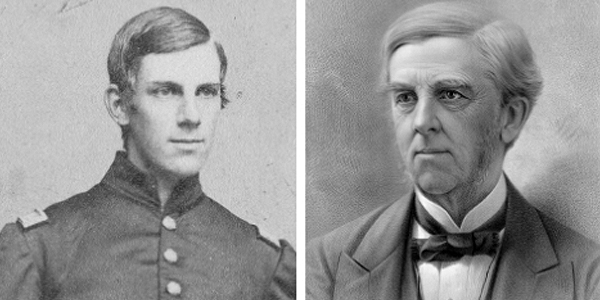

The telegram the Holmes family received brought ominous news. Their son, Captain Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., had been seriously wounded during combat on September 17, 1862 while serving with the 20th Massachusetts. The unit was smashed by a brutal Confederate counterattack in the infamous West Woods at Antietam.

On the morning of September 18, the elder Holmes decided to journey to the battlefield in search of his wounded son. He recorded his trek in an article in The Atlantic, published a few months following his visit to the battlefields of Maryland. The essay is breathtaking in its detail, expressing the emotions that ran through the mind of a desperate father and the horrific sights and smells he experienced as he passed over a landscape shredded by war.

Dr. Holmes passed through the cities of the Eastern Seaboard by railroad. At Baltimore, he headed west on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad and arrived in Frederick, where many of the wounded from the battles of South Mountain and Antietam were being cared for before they were shipped to general hospitals in larger cities. He hired a teamster and a wagon and prepared for a 25-mile trip to the battlefield where his son fell.

As they passed out of Frederick, Dr. Holmes was struck by the sad sights he witnessed. On their westward journey, they passed the human wreckage from the two brutal battles passing on the road toward the makeshift hospitals in Frederick. His account in “My Hunt After the Captain” is riveting:

And now, as we emerged from Frederick, we struck at once upon the trail from the great battle-field. The road was filled with straggling and wounded soldiers. All who could travel on foot,– multitudes with slight wounds of the upper limbs, the head, or face, –were told to take up their beds,–alight burden or none at all,– and walk. Just as the battle-field sucks everything into its red vortex for the conflict, so does it drive everything off in long, diverging rays after the fierce centripetal forces have met and neutralized each other. For more than a week there had been sharp fighting all along this road.

Through the streets of Frederick, through Crampton’s Gap, over South Mountain, sweeping at last the hills and the woods that skirt the windings of the Antietam, the long battle had travelled, like one of those tornadoes which tear their path through our fields and villages.

The slain of higher condition, “embalmed” and iron-cased, were sliding off on the railways to their far homes; the dead of the rank and file were being gathered up and committed hastily to the earth; the gravely wounded were cared for hard by the scene of conflict, or pushed a little way along to the neighboring villages; while those who could walk were meeting us, as I have said, at every step in the road. It was a pitiable sight, truly pitiable, yet so vast, so far beyond the possibility of relief, that many single sorrows of small dimensions have wrought upon my feelings more than the sight of this great caravan of maimed pilgrims.

Dr. Holmes would have found many burial crews like this by the time he arrived on the Antietam Battlefield in search of his son. Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The companionship of so many seemed to make a joint-stock of their suffering; it was next to impossible to individualize it, and so bring it home, as one can do with a single broken limb or aching wound. Then they were all of the male sex, and in the freshness or the prime of their strength. Though they tramped so wearily along, yet there was rest and kind nursing in store for them. These wounds they bore would be the medals they would show their children and grandchildren by and by. Who would not rather wear his decorations beneath his uniform than on it?

Yet among them were figures which arrested our attention and sympathy. Delicate boys, with more spirit than strength, flushed with fever or pale with exhaustion or haggard with suffering, dragged their weary limbs along as if each step would exhaust their slender store of strength. At the roadside sat or lay others, quite spent with their journey…

In total, about 10,000 wounded soldiers made the painful passage from the battlefield to Frederick’s hospitals. Their appearance in Frederick inspired one Pennsylvania newspaper reporter to refer to Frederick as “one vast hospital.”

Captain Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. was not among those stumbling toward Frederick, as his father found out upon reaching the battlefield. Instead, Dr. Holmes found his son on a railcar bound for Pennsylvania from Hagerstown, Maryland. Captain Holmes survived his wounds and returned to service with the 20th Massachusetts. He later became a Supreme Court justice.

“My Hunt After the Captain” stands the test of time as a thrilling, emotional account of a father’s search for his son. Dr. Holmes recorded the thoughts and fears that thousands of families experienced during the Civil War. For many, their journeys to battlefields where sons, brothers, or husbands fell were disappointing and unsuccessful. If their hunts for loved ones failed, families often turned to organizations like the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office which were dedicated to helping families identify the final resting place of those dear to them – a task neither the U.S. Army nor the federal government had taken on in an official capacity.

About the Author

Jake Wynn is the Director of Interpretation at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He also writes independently at the Wynning History blog.

Tags: 20th Massachusetts, Antietam, Frederick, Oliver Wendell Holmes, The Atlantic Posted in: Uncategorized