Fighting Disease with Smell: “Disinfection” during the Civil War

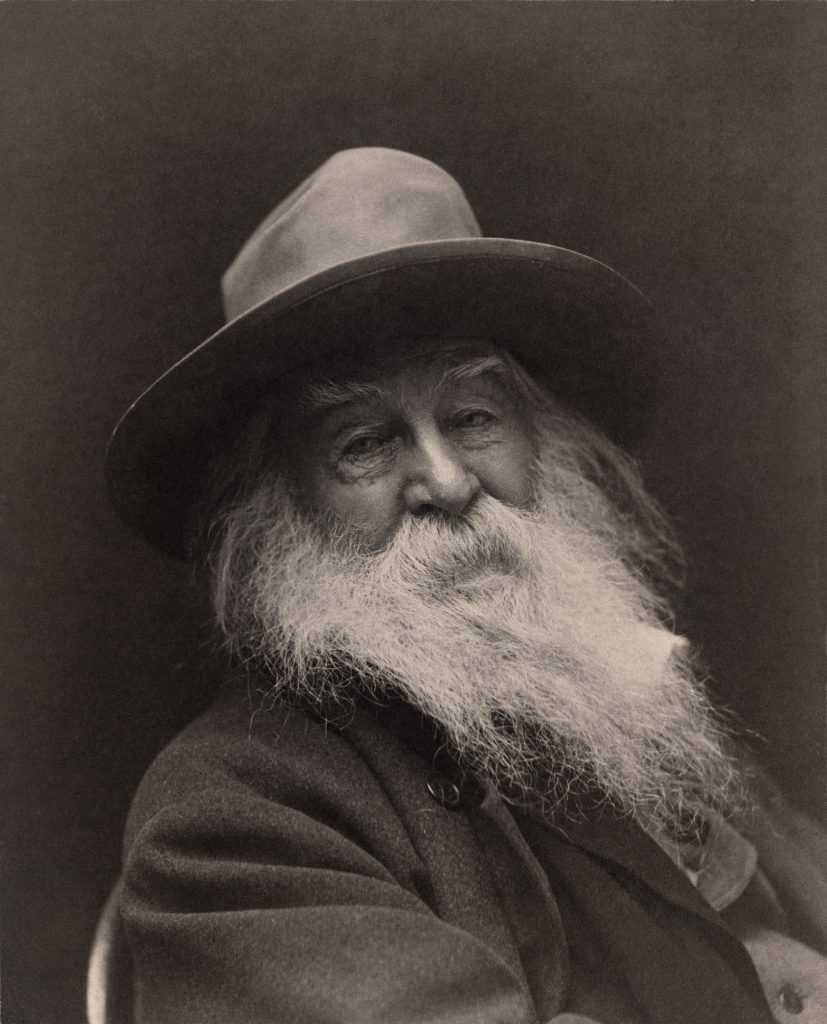

Poet Walt Whitman never forgot the smells of Civil War hospitals where he had nursed wounded soldiers: “The hospitals, with their festering sores, putrid wounds, were enough to fix certain odors forever.” The sharp scent of varnish, which prompted this reminiscence three decades after the war, did not bother Whitman; he had smelled far worse: “…there was a smell that I took for cadavers—it was a terrific odor, extremely disagreeable to me—made me sick in fact.” With time, Whitman learned that the smell was not decomposing bodies, but the carbolic acid that doctors used as a disinfectant. And yet, despite knowing that the “terrific odor” was harmless, Whitman forever associated it with illness and death.[1]

Walt Whitman remarked on the foul orders in Civil War hospitals.

Exposure to chemical disinfectants, and fearful recoil from their strong smells, was a common Civil War experience. As they navigated the spaces of war, soldiers, physicians, and nurses eventually learned to identify the odors of disinfectants, and not to fear their strong smells. This was a dramatic change from life before the war, when Americans focused on fighting foul odors because they believed that those miasmas caused disease. Instead of chemicals, they used fresh air as a disinfectant, throwing open their windows to air rooms, and grew fragrant plants around their homes to “purify” the air with good smells. In spaces where odors might accumulate, like the kitchen, cellar, and outhouse, women used lime—the key ingredient in whitewash—because lime halted decomposition and absorbed odors.

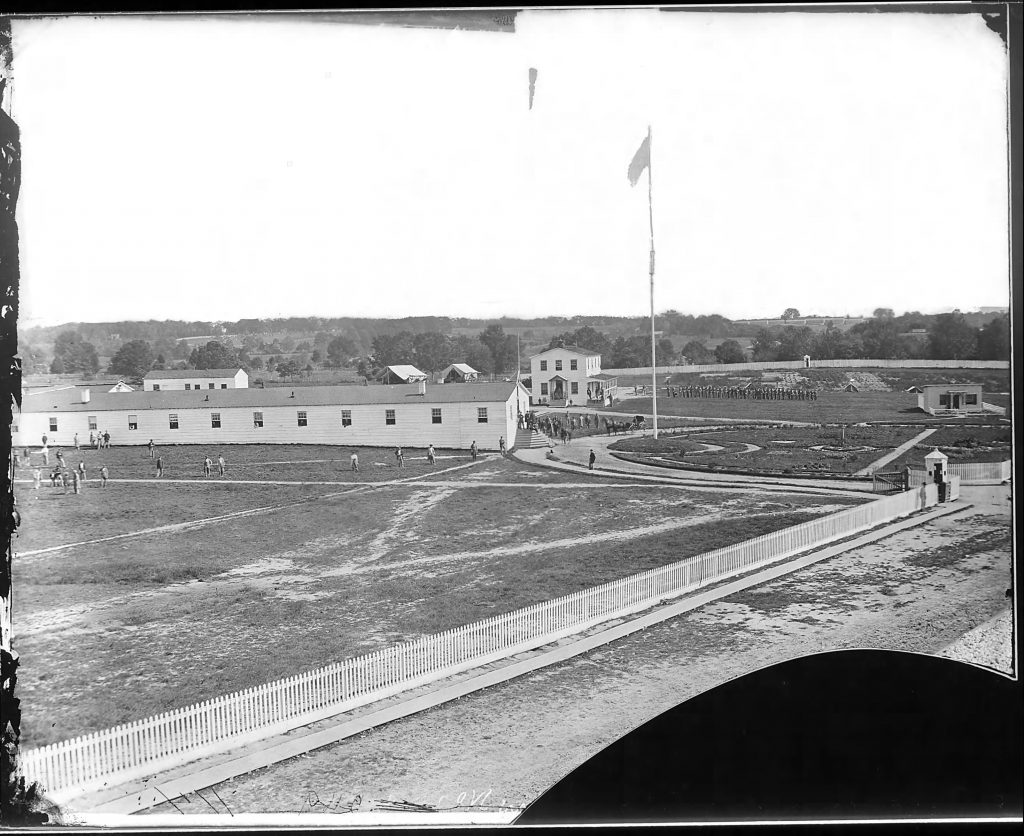

When they could, physicians and nurses used the same methods in Civil War hospitals. They had learned from the British experience in the Crimean War–particularly British nurse Florence Nightingale’s devastating accounts of hospital deaths—that fresh air and good ventilation improved patients’ chances of recovery. Nightingale shared Whitman’s dislike of chemical disinfectants, writing that one should never “depend upon fumigations, ‘disinfectants’ and the like, for purifying the air.” In her Notes on Hospitals, Nightingale insisted that hospitals must be built in a way that enabled the admission and circulation of fresh air.[2]

Harewood Hospital near Washington, note the open windows. Courtesy of the National Archives

In principle, American physicians agreed with Nightingale, and they tried to create well-ventilated hospitals. The United States Sanitary Commission (USSC) consulted with ventilation experts and published circulars about disinfectants that stipulated “there can be no substitute for fresh air to meet the physiological requirements of respiration and health.” It was easy to admit fresh air into pavilion hospitals and hospital tents, but many hospitals did not meet ventilation requirements. Physician Robert Ware reported to the USSC in 1862 about an unventilated hospital: “These rooms are very small and low, and no measures have been taken to open the windows at the top.” Ware observed high rates of typhoid fever and concluded “the atmosphere of the fever ward may be the cause.”[3]

Soldiers and nurses also believed that hospital air would make them sick. When drummer-boy Marcus Woodcock came down with the measles, he worried that he would never recover in the foul-smelling, overcrowded hospital of Columbia, South Carolina: “The stench was horrible from the fact that the beds were simply a continuation of the straw pile[d] around the room…” In the short time that Louisa May Alcott volunteered as a hospital nurse, smells made a strong impression on her: “The first thing I met was a regiment of the vilest odors that ever assaulted the human nose, and took it by storm…and the worst of this affliction was, every one has assured me that it was a chronic weakness of all hospitals, and I must bear it.” Alcott bore it by sprinkling herself with lavender water, thinking that she would not get ill if she inhaled the sweet scent of lavender rather than hospital air.[4]

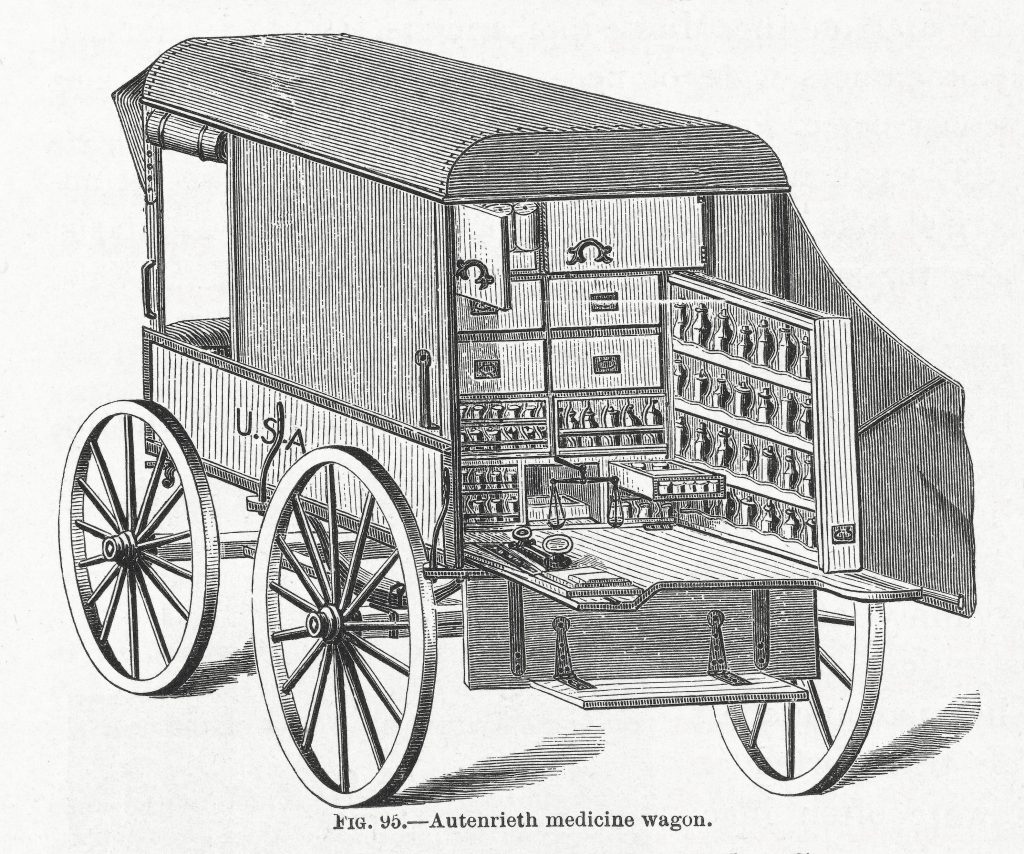

Lavender water was not strong enough to overpower the smells of illness and death, so physicians turned to stronger chemical disinfectants. Where fresh air was unavailable, because a hospital was poorly ventilated or its windows admitted battlefield stenches, the United States Sanitary Commission recommended alternatives that would eliminate foul odors and thus the dangers of miasma. Guidelines categorized these disinfectants by how they acted on odors. Some, like nitrate of lead and chloride of zinc, arrested decomposition and thereby halted odor production. Charcoal and sulfate of lime were useful because they directly absorbed noxious effluvia. But carbolic acid, the disinfectant that turned Whitman’s stomach, was preferable because it was so effective. As the Sanitary Commission noted, carbolic acid was “antiseptic and deodorant; capable of a great variety, extent and economy of applications, and act[s] with considerable agency and permanency.”[5]

Medicines like Chloride of Zinc were standard issue on Autenrieth medicine wagons like this. Courtesy of Wiki Commons

Because Americans did not know about germs and thought the air conveyed illness, they used disinfectants in very different ways from those we employ today. Civil War doctors did not sterilize surgical instruments or wounds, as physicians would later learn to do, but sprinkled disinfectant substances throughout hospital spaces to purify the air. As a result, the smells of disinfectants dominated the air of hospitals, making these strong odors synonymous with ill health and the danger of death. When Americans returned to their homes and civil life from wartime hospitals, they carried with them new knowledge about disinfectants and a renewed appreciation for fresh air.

Learn more in this interview with Dr. Melanie Kiechle, the post’s author:

Read more about the smells of the nineteenth century, and how Americans dealt with their fears of miasma, in Smell Detectives: An Olfactory History of Nineteenth-Century Urban America.

Want to learn more? Follow us on Facebook and Twitter to discover more stories from Civil War medicine!

Become a museum member and support our educational programs and research like this.

About the Author

Melanie Kiechle is a historian of the nineteenth-century United States. Her interests include culture, environments, cities, health, science, and smells. Her book, Smell Detectives: An Olfactory History of Nineteenth-Century Urban America, uncovers how city residents used their noses to understand, adjust to, and fight against the environmental changes created by rapid urban growth and industrialization. She is an associate professor of history at Virginia Tech, where she teaches courses on United States history, environmental history, and the history of science and medicine.

Endnotes

[1] Walt Whitman qtd. In Horace Traubel, With Walt Whitman in Camden (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1992), 7:168-69, https://whitmanarchive.org/criticism/disciples/traubel/WWWiC/7/med.00007.90.html

[2] Florence Nightingale, Notes on Nursing: What It Is, and What It Is Not (New York: D. Appleton and Co., 1860), 23.

[3] Elisha Harris, “Sanitary Hints: Special Disinfectants and Their Applications,” The Sanitary Commission Bulletin (New York, 1866), I:59-60; Dr. Robert Ware to USSC, March 9, 1862, Box 15, Folder 17, Item no. 545, US Sanitary Commission Records, Washington, DC, Archives (MssCol 22261), Manuscript and Archives Division, New York Public Library.

[4] Kenneth W. Noe, ed., A Southern Boy in Blue: The Memoir of Marcus Woodcock, 9th Kentucky Infantry (U.S.A.) (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1996), 37-38; Louisa May Alcott, Hospital Sketches: An Army Nurse’s True Account of Her Experiences during the Civil War (1863; repr., Bedford, MA: Applewood Books, 1991), 27.

[5] Harris, “Sanitary Hints,” 60.

Tags: Civil War Hospitals, Civil War Medicine, disease, Florence Nightingale, Melanie Kiechle, Sanitary Commission, Walt Whitman Posted in: Uncategorized