A Hole in the Head–Civil War Trephination

Neurosurgery is one of the most difficult and complex types of surgery. The brain and nervous systems control all life-sustaining processes in the body and the smallest mistake can lead to countless post-surgical complications. The birth of American neurosurgery can at least be traced to the Civil War but the tradition of opening the skull has been going on for thousands of years. Some of the earliest examples of trephination and brain surgery come from Peru circa 400 BC while also being observed throughout Europe during the medieval period.[1] Originally, the technique is believed to have been used for headaches, trauma to the head, and to release evil spirits from the body by either cutting or drilling a hole in the skull.

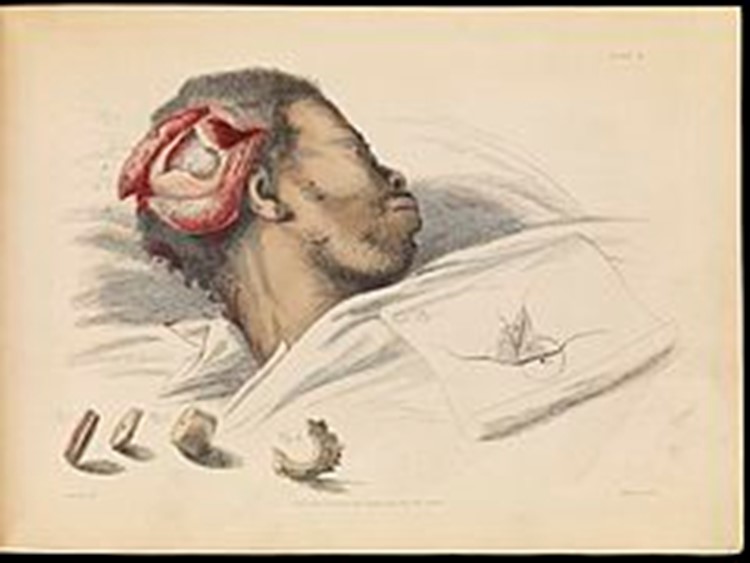

The device used for trephination, known as a trephine, has an interchangeable wooden handle that can be placed on trephines of assorted sizes, and a rotating metal cutting head used to cut a hole in the skull. The trephine has a metal spike in the center of the cutting head to keep the material being cut in place and to secure its removal. Other implements used in the trephination process are a scalpel, bone brush, and a Hey’s saw.

First the surgeon would sedate the patient and begin to use the scalpel to slowly separate the skin from the skull. Once a sufficient space was created, the surgeon would then use the trephine to cut a hole near the wound or use the Hey’s saw to scrape away at the skull. If done correctly, the dura mater is left untouched, and the pieces of fractured bone or the bullet are removed. Trephination was one of the more dangerous surgeries that carried some of the most risk if done incorrectly – leading to its high mortality rate. Around 200 instances of trephination were performed during the Civil War with a staggering 57% mortality rate.[2] Despite this, many of those that survived lived fairly normal lives with little neurological deficits.

During the Civil War, there was debate within the medical community over the effectiveness of trephination in patient survival. While it was a risky procedure, there were instances where it was necessary. Dr. John J. Chisholm was one of the doctors against trephination. Chisholm used a more conservative approach when appropriate but did recognize that in cases of a depressed skull fracture, trephination could save the patient’s life.[3] Dr. Chisholm and his counterparts, who advocated for caution when facing injuries to the head, recalled the experiences of trephination in the Crimean War where some reported the mortality rate of the procedure to be 100%.

In the post-war years, renowned Civil War surgeon Samuel W. Gross published a paper comparing treatment outcomes of gunshot wounds to the skull using trephination and the conventional method of treatment. The conventional method consisted of a more conservative approach where an operation would only be performed if symptoms of compression of the brain were showing[4]. Dr. Gross found “in his examination of 160 cases in which the trephine was employed that the death rate was 60.62 percent. By contrast, in the 573 cases in which the expectant method was used the mortality rate was 74.34 percent.”[5] While trephination still carried a considerable risk, Dr. Gross found that the mortality rate was much lower, and patients often survived more than the expectant method.

Corporal John Colvin, Company B, 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry suffered a saber cut to the forehead on January 2, 1864. Corporal Colvin’s case was described in this way “the right parietal bone was badly fractured near the sagittal and frontal sutures. About one square inch of the bone being loose, was removed, together with several spiculae, and a sharp projection was removed by Hey’s saw.”[6] Hey’s saw was one of the several instruments developed in surgeries of the cranium. Corporal Colvin experienced one delirious night followed by no presented symptoms for the duration of his stay in the Cavalry Corps Hospital. He was returned to his regiment several weeks later on January 28.

On October 3, 1864, Private William H. Lowey, Co. C, 6th Tennessee Cavalry was wounded near Memphis, Tennessee receiving a “punctured fracture of the right parietal bone, near its superior posterior angle, produced by a blow of a musket, the hammer passing through both tables of the cranium.”[7] His treatment began in his regimental hospital but was later moved to Gayoso Hospital ten days later when he began to exhibit several symptoms of a compressed skull fracture. Acting Assistant Surgeon Julius Brey removed a circular portion of the skull near the wound site and examined the brain. Brey’s examination found no visible injury to the dura mater, the membrane that surrounds the brain and spinal cord. Fragments of the skull were removed, and cold water dressings were applied to the wound area. Private Lowey did become restless for several days and at nights, on occasion, delirious. Doctors prescribed Private Lowey extract of Cannabis Indica which did improve some of his symptoms. On October 18, Private Lowey came down with a case of pneumonia and cerebral hernia on November 3. Two weeks later on November 17, Private Lowey died of his wounds after entering a coma.[8]

Some of the first blood to be spilled during the Civil War happened in Baltimore on April 19, 1861. One week after the attack on Fort Sumter by South Carolina Confederates, the 6th Massachusetts disembarked their train in Baltimore to head to another train for Washington. During this period between trains, southern sympathizers crowded the 6th MA and began throwing stones at the men along Pratt Street. The soldiers turned and fired into the crowd; four soldiers died, thirty-six were wounded, and twelve civilians were killed.

One of the soldiers killed during the riot was Private Sumner H. Needham, Co. I, 6th Massachusetts. Private Needham was struck in the forehead with a brick and was taken to Baltimore University where he was examined by future Surgeon General William A. Hammond who determined that a trephine needed to be used. Dr. Hammond performed the operation, however, it was not successful and Private Needham died several hours later.[9] The rest of the wounded men from the regiment were taken to the US Capitol Building and were treated by former teacher and future world-class humanitarian Clara Barton.

Dr. William Hammond, after his service in the Civil War, became a founding member of the American Neurological Society and went on to shape the future of neuroscience and neurosurgery. Trephination is one of the oldest surgical procedures in human history and it is still used today. Modern neurosurgeons often perform what is known today as “burr holes.” The purpose of a burr hole is to relieve pressure on the brain when intracranial pressure builds up due to increased levels of fluid in and around the brain. Over the past 160 years, the field of neuroscience has evolved with technological advancements in imagery, medicines, and techniques. Neurosurgery was a delicate and fragile process during and before the Civil War, and while it still is today, modern technological advancements have reduced the risks of death or neurological deficits by a considerable amount.

Sources

[1] Kushner, David S., John W. Verano, and Anne R. Titelbaum. “Trepanation Procedures/Outcomes: Comparison of Prehistoric Peru with Other Ancient, Medieval, and American Civil War Cranial Surgery.” World Neurosurgery. Elsevier, March 29, 2018. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1878875018306259?via%3Dihub.

[2] Bollet, Alfred J. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Tucson: Galen Press, 2002. Pg. 168

[3] Bollet, Alfred J. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Tucson: Galen Press, 2002. Pg. 168-169

[4] Bollet, Alfred J. Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs. Tucson: Galen Press, 2002. Pg. 168

[5] Devine, Shauna. “Practice and the Science of Medicine.” PBS. Public Broadcasting Service, February 1, 2016. http://www.pbs.org/mercy-street/blogs/mercy-street-revealed/practice-and-the-science-of-medicine-and-the-emergence-of-william-hammond/.

[6] The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Vol 2. Part. 2. Washington: G.P.O., 1888. Pg. 17

[7] The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Vol 2. Part. 2. Washington: G.P.O., 1888. Pg. 58

[8] The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Vol 2. Part. 2. Washington: G.P.O., 1888. Pg. 58

[9] The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion. Vol 2. Part. 2. Washington: G.P.O., 1888. Pg. 58

About the Author

Michael Mahr is the Education Specialist at the National Museum of Civil War Medicine. He is a graduate of Gettysburg College Class of 2022 with a degree in History and double minor in Public History and Civil War Era Studies. He was the Brian C. Pohanka intern as part of the Gettysburg College Civil War Institute for the museum in the summer of 2021. He is currently pursuing a Masters in American History from Gettysburg College and the Gilder Lehrman Institute.

Tags: Civil War Medicine, trephination Posted in: Battlefield Medicine, Medical Advancements